Blockchain technology offers some unique properties, such as achieving consensus among unknown actors and providing a strong incentive mechanism for honest behavior. However, building real-world applications on blockchain technology can be challenging.

The first challenge of building applications on the blockchain is security. A blockchain’s security increases as the number of network participants grows. As a result, spinning up a small application-specific blockchain with just a few stakeholders does not provide the same security level as utilizing an established one with thousands of nodes.

A blockchain’s security model, in turn, depends on utilizing a token with real value, tradeable on established markets. This holds in the case of Proof of Work blockchains in which miners get rewarded for their computational power with a token, as well as in Proof of Stake blockchains where a validator’s security deposit needs to have economic weight. A native token with real-world value, thus incentivizes users to provide additional security to the network by mining or staking and allows applications to transfer value easily.

Building directly on top of a public blockchain comes with other challenges. First, blockchains are not well suited for handling large amounts of data and transactions. Second, deploying a new feature, which might be necessary for a given application, would require consensus-building among the entire community of stakeholders. If only a small subset of participants benefit from the feature, it is unlikely to be implemented. Lastly, the codebase would quickly become unmanageable if features and applications were built directly on the mainchain.

In summary, the three major roadblocks to building on public blockchains are security and scalability, the burdensome governance processes required for introducing new functionality, and the lack of a token with real-world value.

Meet sidechains. Sidechains benefit from the decentralization and security of the underlying main blockchain and maintain the flexibility to solve highly specific use cases.

Adding and removing features onto a sidechain does not depend on the mainchain’s community consensus since new features will only affect sidechain users. Also, new features can be added to separate sidechain ledgers, reducing stress on the mainchain.

Sidechains cannot derive 100% of their security from the mainchain; they still require dedicated nodes. But incentive mechanisms can be constructed that lead to existing mainchain nodes also supporting sidechains built on top of it.

SIDECHAINS

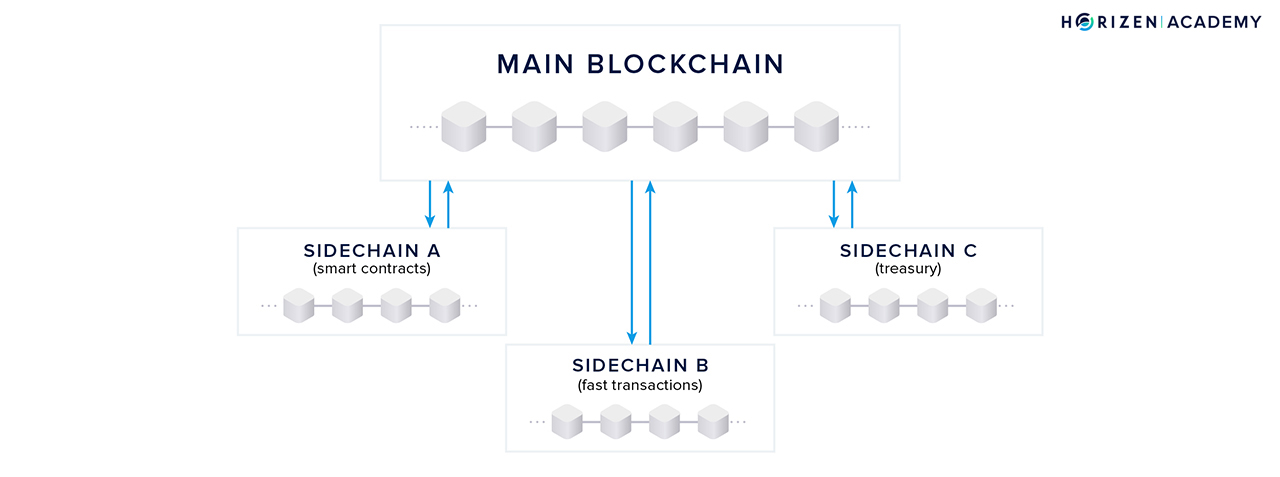

Having the ability to deploy sidechains will dramatically enhance the possibilities of building on top of existing public blockchains. One of the first use-cases of a sidechain for the Horizen project will be the Treasury, moving the organization a step closer to its goal of becoming a decentralized autonomous organization, or a DAO.

When you enable sidechains, you allow a number of different blockchains to run in parallel. A sidechain is a blockchain in and of itself with the added feature of being interoperable with the main blockchain. Transactions are the most common interaction with a blockchain facilitating a cryptocurrency, such as our current Horizen blockchain. The Engineering team at Horizen, led by Alberto Garoffolo, has proposed a sidechain construction based on proof-of-stake principles.

The most important part of building our sidechain construction is the cross-chain transfer protocol. This innovation is a new backward transfer protocol that allows transactions from one of the possibly many sidechains back to the mainchain, without the mainchain having to track the sidechain and without introducing a centralized federation of validators. While a reference implementation of a sidechain consensus protocol will be provided, a wide range of sidechain consensus protocols will be possible.

Sidechains are a concept that people have been looking into for a while now. The first proposal of sidechains was developed by Back et al. in 2014 and several teams are working to implement them as a solution to the problems of scalability and interoperability.

What is a Sidechain and Why Would You Want One?

When Back et al. introduced the sidechain concept in 2014, they provided the following definition along with it:

“A sidechain is a blockchain that validates data from other blockchains. […] A pegged sidechain is a sidechain whose assets can be imported from and returned to other chains; that is, a sidechain that supports two-way pegged assets.” A. Back et al. - Enabling Blockchain Innovations with Pegged Sidechains, 2014

In other words, a sidechain is a blockchain that can communicate and interoperate with one or more other chains. When you hear the term sidechain today, people are mostly talking about pegged sidechains, which allow you to transfer assets back and forth between chains.

So What is the Benefit of This Technology?

Most blockchains facilitating cryptocurrencies use the proof-of-work consensus algorithm and have incorporated the core functionalities of the Bitcoin protocol. Therefore, they inherited a lot of the constraints from the code created by Satoshi Nakamoto. This includes limited throughput, high latency, and a limited ability to scale. Sidechains present an option to help overcome some of these technological shortcomings, but besides opening doors to only potential technical leaps, they also touch on the topic of governance.

As debates across the recent years have shown, making changes to the codebase in decentralized projects tends to be a cumbersome process. This is arguably a feature, not a bug. Stability, not in regards to token price but code, is crucial, especially for projects such as Bitcoin, and the overall security of the protocol benefits greatly from the careful consideration of every change applied to the system.

Sidechains offer a mechanism to implement features on top of a first layer protocol without compromising the security or stability of said protocol. After an initial fork that includes the capability to deploy sidechains and introduces a way to transfer assets from the mainchain to the sidechain and vice versa, a number of parallel chains can be built, each serving a different purpose, without having to build consensus for each individual feature.

It is important to note that the initial change to the codebase enabling the deployment of sidechains and cross chain transfers has to be done carefully and possible solutions should be evaluated with great caution. If a project manages to deploy those features, then developers can start playing around and build on top of projects where changes to the protocol traditionally required consensus building for months, or even years. Ideally, the sidechain implementation will give developers on the sidechain many degrees of freedom while eliminating the possibility to compromise mainchain security. If a user has no need to use a particular sidechain, he doesn’t have to care about the security of those sidechains.

What Can You Do with a Sidechain?

As we said earlier, many teams are looking into the technology of sidechains for a variety of purposes. The team behind Rootstock is working on a way to provide smart-contract functionality on top of Bitcoin. They refer to their sidechains as secondary chains. Polkadot, naming its sidechains Parachains, aims to connect permissioned and public blockchains. The general idea of Plasma is also based on sidechains, or child blockchains, and here the main goal is scaling. Drivechains are meant to enable BTC to be moved to other software applications, like different public blockchains.

You could make a case of distinguishing between sidechains and drivechains as discussed by Rootstock. We will pick up on their distinction shortly when talking about how sidechains work.

The general idea is the same, and satisfies the broad definition of a pegged sidechain that Back et al. provided about eight years ago.

Critics of the sidechain concept like to point out that most sidechain implementations currently rely on a set of validators to facilitate cross-chain transactions. Sidechain constructions are oftentimes called trust-minimized instead of trustless. The risk comes down to the ability of the trusted validators to censor transactions from main to sidechain, and vice versa. Our protocol addresses this issue in an elegant way.

Use Cases for Sidechains

Scalability

Use cases for sidechains include data or transaction-heavy applications.

A transaction-intensive use case could be a real-time in-game payment system in which users can earn and spend tokens. A traditional blockchain would not be suited to handle the load if the system had several thousand simultaneous users and logged all rewards on the mainchain. A sidechain with short block intervals and a centralized consensus mechanism to verify transactions efficiently is a much more feasible approach.

A data-intensive use case could be a supply chain tracking system. If this system was used by producers, logistic companies, retailers, and other third parties, the amount of data would soon exceed the limits most public blockchain nodes are willing to handle. A dedicated sidechain with additional data fields for storing product-specific metadata can be a possible solution. The blocksize would likely be increased to accommodate more data storage per time unit.

Governance

Deploying a domain-specific sidechain would allow quick feature iterations by circumventing the consensus-building process used on a public network. This decoupling protects the mainchain because bugs resulting from new feature deployment would only affect the destination sidechain.

Horizen is evaluating which sidechains to develop first. Options include sidechains supporting sophisticated, Turing complete smart contracts, near instant payment settlements, or a sidechain handling the Zen Blockchain Foundation treasury funds.

While Horizen’s mainchain does not support custom tokens, a sidechain could provide this functionality. Any developer is free to build and deploy sidechains on Horizen’s mainchain without permission and without the risk of breaking things.

Sidechains are an essential technological step to expanding the capabilities of distributed ledgers and making them suitable for a broader range of use cases.

History of Sidechains

Sidechains are a concept people have been talking about for years. The first sidechain proposal was written in 2014, and since then, several teams have implemented them in different ways.

Pegged Sidechains

As stated before, the first mention of sidechains came from Adam Back et al. in a paper released in 2014. “Enabling Blockchain Innovations with Pegged Sidechains” introduced the technological concept of pegged sidechains that allow the transfer of assets from one chain to another. The paper introduced much of the terminology around sidechains still used today.

Symmetric vs. Asymmetric Peg

The authors distinguish between symmetric and asymmetric pegs. In a symmetrically-pegged sidechain construction, the mainchain monitors the sidechain and vice versa. Because both systems are aware of each other, cross-chain transfers work the same both ways - they are symmetric.

In an asymmetric two-way peg construction, the sidechains monitor the mainchain, but the mainchain does not track the sidechain. In this construct, the transfer of assets from mainchain to sidechain, a Forward Transfer, is simple because sidechain nodes can verify incoming transactions themselves. The transfer of assets back to the mainchain, a Backward Transfer, is more complex. The mainchain needs to “be told” about incoming transfers and relies on some previous verification of transactions. One of the conclusions of the paper reads as follows:

“The key observation is that any enhancement to Bitcoin Script can be implemented externally by having a trusted federation of mutually distrusting functionaries evaluate the script and accept by signing for an ordinary multisignature script.” - Enabling Blockchain Innovations with Pegged Sidechains

In other words, an asymmetric sidechain can support most conceivable applications and internal transactions, as long as a group of certifiers verifies and forwards relevant transactions to the mainchain in a format it supports.

An asymmetric sidechain construction is desirable because it allows the deployment of many different sidechains without requiring the consensus of the community. A symmetric sidechain would require the mainchain to update with each new sidechain deployment - rendering the reduced governance benefit useless.

Proof of Authority Sidechains

A notable sidechain construction based on the Ethereum blockchain is built by the POA Network team. The authors Barinov, Baranov, and Khahulin propose “an open, permissioned network based on Ethereum protocol with Proof of Authority consensus by independent validators.”

The design is asymmetric: Sidechains monitor the mainchain but not vice versa. They hypothesized that deploying sidechains on top of a smart contract enabled blockchain is simpler than deploying on a Bitcoin-based system. They purported that forward and backward transfers could be handled via smart contract logic instead of via the core protocol.

Nonetheless, each sidechain in the POA Network depends on a group of individuals, verifying backward transfers and broadcasting them to the Ethereum mainchain.

“Each project deploying the bridge must account for its own validators. It’s absolutely necessary for the project(s) to identify the set of individuals/nodes assigned to validate the bridge transactions. It’s important to note validators are required as part of any bridge launch.” - POA Network, Introducing the ERC20 to ERC20 TokenBridge

Other Sidechain Constructions

Several teams are working on other sidechain constructions. Drivechains are sidechains built on the Bitcoin network in which mainchain miners perform the verification of transactions from drive to mainchain.

The most significant number of sidechain protocols are built on the Ethereum network. Besides the POA network, Plasma is another noteworthy example. It was presented by Joseph Poon and Vitalik Buterin in 2017 and is based on smart contracts deployed on the Ethereum main net.

The sidechain constructions mentioned above assume one of two things:

- The design is symmetric, requiring the mainchain to monitor all sidechains to verify backward transfers The construction is asymmetric, and the mainchain relies on some sort of certifiers to verify and broadcast transactions from the sidechains to the mainchain.

A first iteration of Horizen’s sidechain construction also relied on certifiers to sign backward transfers batched in withdrawal certificates.

Why Does Horizen Look at Sidechains?

The Horizen blockchain project has set itself ambitious goals. We plan on including features such as a treasury system for the DAO, in cooperation with IOHK. Work continues on a decentralized solution for tracking Secure and Super Nodes, and handling their rewards, as well as developing a Block-DAG protocol to increase transaction throughput.

You can probably see the benefits of developing a sidechain first as some of these functionalities would require significant modifications of the core client if implemented directly into the existing codebase. Building new features and making changes to the protocol, even if they are small, is not just challenging from the aspect of building consensus around them; it also comes with security risks. Every addition has to be considered carefully.

The idea is to implement a robust sidechain model, one that simplifies adding new features, and use that process to expand the Horizen ecosystem afterward. Sidechain implementations will be completely decoupled from the mainchain and can run entirely different consensus algorithms. This way, it would be possible to run the sidechains facilitating the treasury and node-tracking system with a Proof-of-Stake like consensus protocol, while maintaining the mainchain with a more “traditional” Proof-of-Work consensus mechanism.

How Does It Work Now?

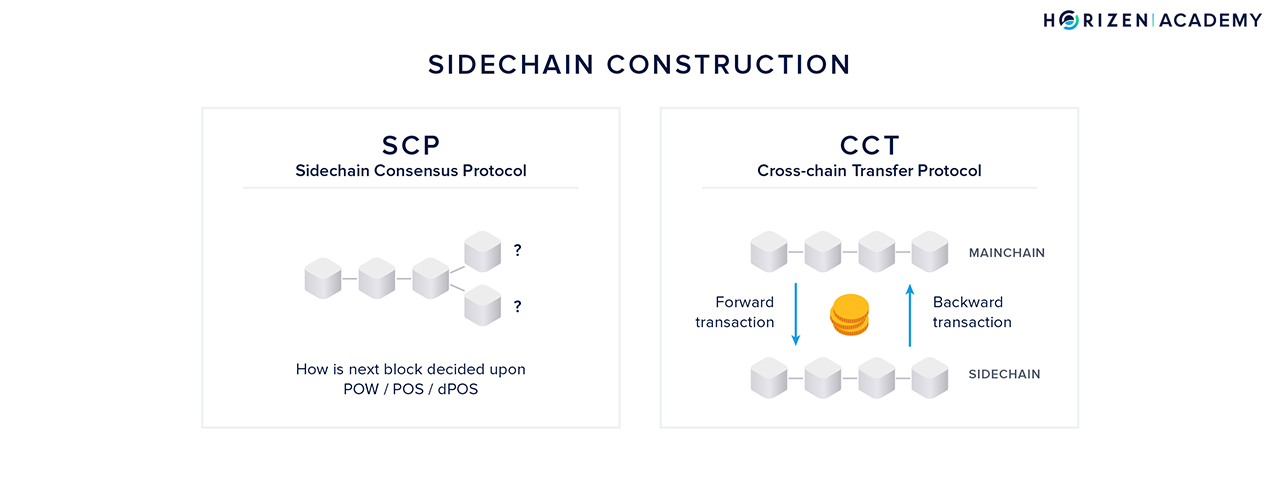

The construction of the sidechain model consists of two parts:

- The sidechain consensus protocol — SCP

- The cross-chain transfer protocol or 2-way peg — CCT

The sidechain consensus protocol governs how the network agrees on new blocks and therefore on the history of transactions. The cross-chain transfer protocol determines how assets can be sent from the mainchain to a sidechain and vice versa.

The CCT consists of two sub-protocols that we want to introduce shortly.

The first sub-protocol deals with forward transactions, which are transactions from mainchain to sidechain. The second sub-protocol deals with backward transactions, which are transactions from sidechain to mainchain.

The first design decision to make is whether the mainchain should be aware of the sidechains. The team led by Alberto Garoffolo decided to develop the SCP and CCT independently of each other.

The CCT protocol is to be unified and fixed by the mainchain logic so that all sidechains will use the same CCT protocol. The SCP protocol will be completely decoupled from the CCT and mainchain logic in general so that a sidechain developer is free to choose the SCP protocol depending on the needs.

Although a number of different sidechain consensus protocols are possible, we will outline the proposed reference implementation of the SCP that is based on Ouroboros. It is a Proof-of-Stake consensus protocol that makes use of the concept of delegation. After that, we will talk about the Cross-Chain Transfer Protocol.

The Sidechain Consensus Protocol - SCP

The proposed SCP is based on the Ouroboros Protocol developed by IOHK for the Cardano project with some slight modifications. It is a Proof-of-Stake based consensus protocol that makes use of the concept of delegation and generally works like this:

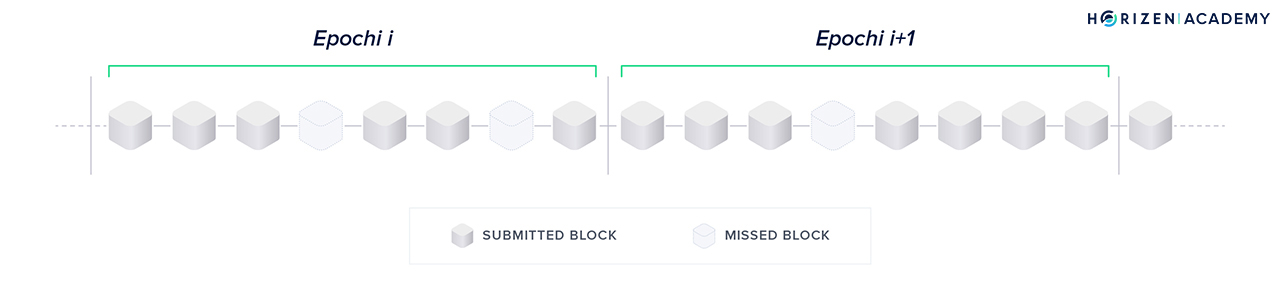

- Time is divided into epochs of k slots. It is not specified yet, but let’s assume k will be 8 for the sake of the argument and matching the graphic below.

- Each slot represents the opportunity to create a sidechain block within a certain period of time. Research suggests 20 seconds is a reasonable amount of time to allow network synchronization across the globe. During an epoch up to k blocks will be forged.

- There is a slot leader for each slot. The slot leader is authorized to generate a block within this time period.

- Before an epoch begins, there is a Slot Leader Selection Procedure that assigns one slot leader per slot for the next epoch. In our example, 8 slot leaders will be selected per selection procedure/epoch.

- If a slot leader misses their time slot to forge a block, the next slot leader will include the transactions that weren’t included previously.

Modifications of the Ouroboros Protocol

The security of software is usually evaluated under certain assumptions. Consensus protocols are no different.

POW consensus is based on the assumption of an honest majority in hashing power. The core assumption the Ouroboros POS protocol security is based on is a random Slot Leader Selection Procedure. No party should be able to predict who will be the assigned slot leader during a given time period.

To achieve this goal, a source of randomness is needed and creating true randomness is harder than one might think. The original Ouroboros POS protocol introduced a coin-tossing protocol based on verifiable secret sharing to generate randomness. The proposed modified solution leverages the POW mainchain for this. It is a simple, yet effective solution.

The randomness is derived from the smallest block hash on the mainchain in a given period of time. For this to work, the set of eligible certifiers will be fixed, before the randomness generation period starts. A significant share of hashing power would be needed to corrupt this mechanism. Under the assumption of an honest majority in hashing power on the mainchain, this should be infeasible and economically unprofitable. A formal analysis of such an attack will be conducted separately.

Another modification to the original Ouroboros implementation regards the references to the mainchain included in the sidechain blocks. We will talk about this in the context of the Cross-Chain Transfer Protocol when introducing the concept of full referencing.

Liveness and Persistence

Garay, Kiayias & Leonardos say that the standard procedure of proving blockchain consensus protocol security requires demonstrating the ability of the protocol to satisfy two fundamental properties of a distributed ledger: liveness and persistence.

“Persistence states that once a transaction goes more than k blocks “deep” into the blockchain of one honest player, then it will be included in every honest player’s blockchain with overwhelming probability, and it will be assigned a permanent position in the ledger.” — Garay, Kiayias & Leonardos, 2014

Persistence is closely related to the property of immutability.

“[…]Liveness says that all transactions originating from honest account holders will eventually end up at a depth more than k blocks in an honest player’s blockchain, and hence the adversary cannot perform a selective denial of service attack against honest account holders.” — Garay, Kiayias & Leonardos, 2014

This is closely related to the property of censorship resistance. Note that this is a different k from the one describing the number of blocks per epoch.

Properties like liveness and persistence are proven under a set of assumptions such as an honest majority among participants. An exhaustive list of these assumptions and their definitions can be found in the original Ouroboros paper.

Enabling Different SCP’s

The motivation behind developing the SCP and CCT separately was to enable a variety of possible SCP’s. Although the following description of the Cross-Chain Transfer Protocol takes up on a few concepts of the adapted Ouroboros protocol described above, it can be combined with a number of other consensus mechanisms. Horizen is currently looking into a Block-DAG (Directed Acyclic Graph) structure. The interoperability between another POW sidechain or a Block-DAG mainchain and the CCT protocol will be subject to additional research.

The Cross-Chain Transfer Protocol - CCT

“The CCT protocol is the most important part of the sidechain construction since it defines the overall structure of the communications between MC and SC.” - Sidechain Whitepaper ; Garoffolo, Viglione

We already mentioned the two sub-protocols of the CCT:

The first sub-protocol deals with forward transactions, which are transactions from mainchain to sidechain.

The second sub-protocol deals with backward transactions, which are transactions from sidechain to mainchain.

Forward Transactions and Full Referencing

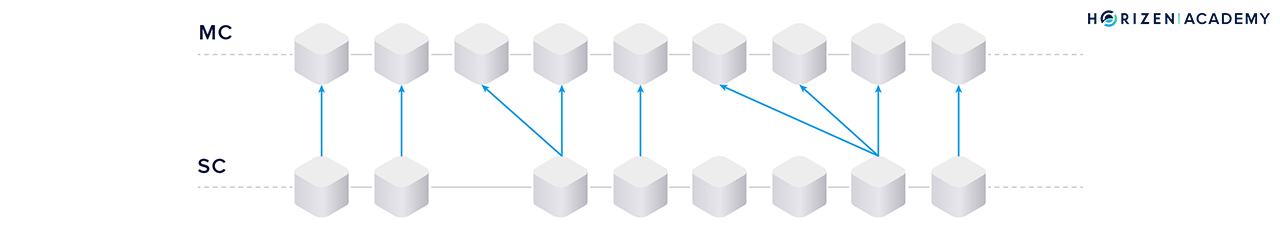

It is the goal to enable cross-chain transfers, so there must be a form of communication between chains. The sidechain needs to be aware of all transactions on the mainchain that are sending assets to an address on the sidechain (forward). There needs to be a mechanism for the mainchain to verify incoming backward transactions.

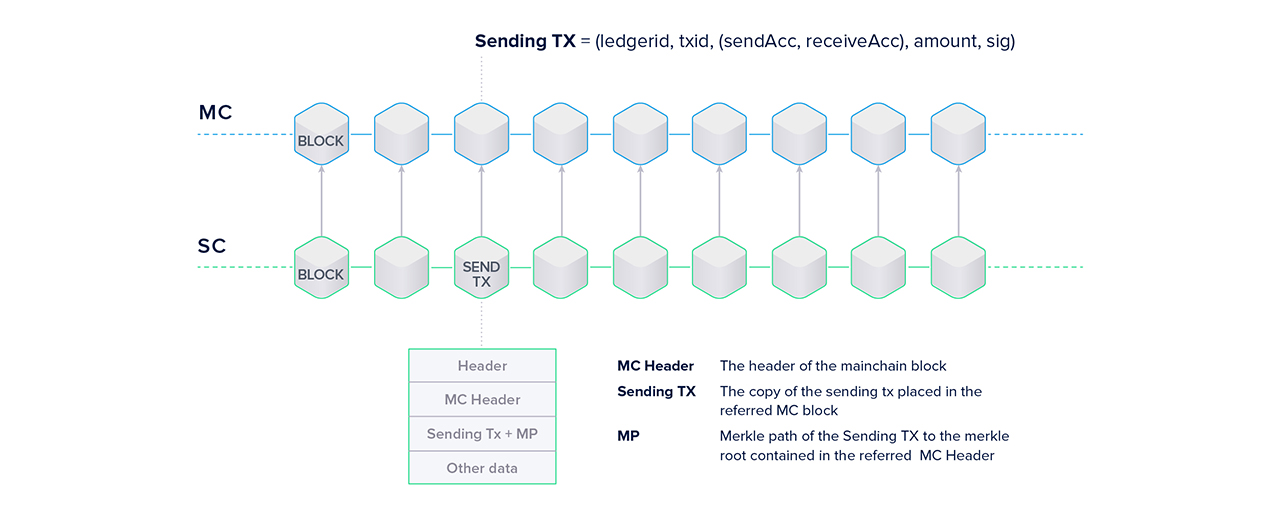

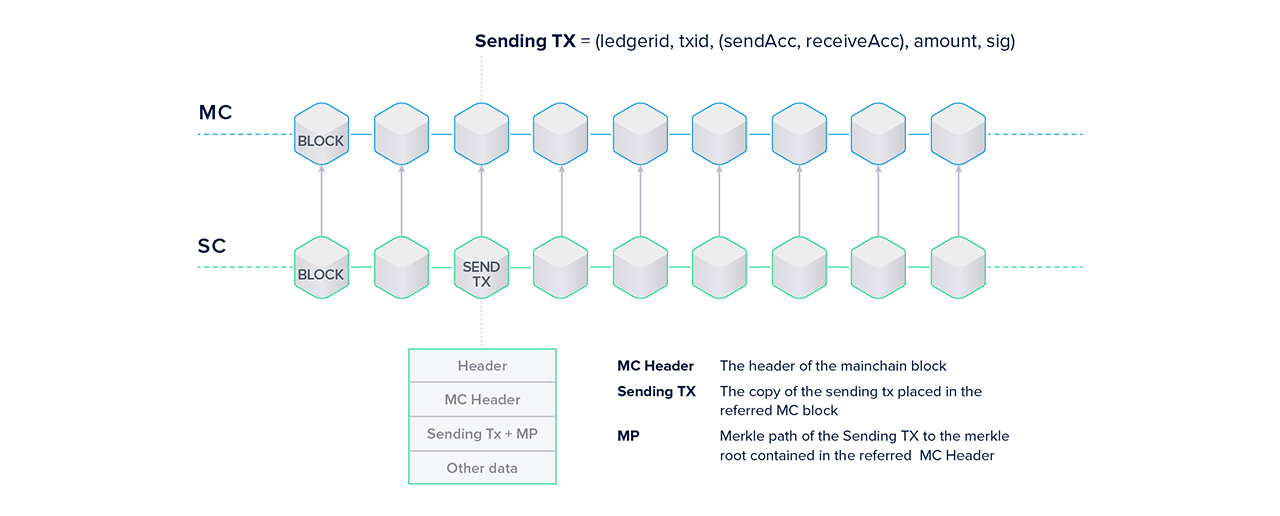

The enablement of forward transactions is achieved through full referencing. It solves two problems at once: enabling transfers from the main- to the sidechain in a straightforward fashion and dealing with finality (or lack thereof).

“Full referencing implies that the sidechain blocks contain the full chain of the mainchain block references. Even if some block forger missed his opportunity to include a reference to the newly generated MC [mainchain] block, some of the following block forgers will include the missed mainchain reference.” - Sidechain Whitepaper; Garoffolo, Viglione

So how does full referencing achieve the goals mentioned above? The references can be one of two things:

- If the mainchain block contains no transaction to the sidechain under consideration, only the block hash is used as a reference.

- If there are one or more forward transactions in the last block, the entire block header, the forward transaction(s) and the Merkle path of the transaction(s) are used as a reference.

Sidechain nodes can easily verify the transfers by including the block header and Merkle path of forward transactions. You could think of the two ledgers, sidechain and mainchain, as two separate books. Since the sidechain bookkeepers constantly monitor the main(chain) book, they can easily add cross chain transactions to their book. By including the transactions together with their Merkle paths and the corresponding block header, every entity on the sidechain will be able to verify the transaction is valid for themselves without having to check in with the mainchain.

Enabling the forward transfer protocol implies making changes to the current mainchain logic. A new type of transaction needs to be introduced that burns coins and provides a set of metadata which allows the user to claim the same amount, minus the TX fee, of newly created coins on the sidechain. The same goes for backward transactions: coins on the sidechain are burned and an equivalent amount minus TX fees created on the mainchain. A construction with a locking and unlocking procedure is also feasible.

The other problem that is solved relates to the finality issue with POW chains using Nakamoto Consensus. It is possible for a valid forward transaction to be included in a mainchain block at first, but the block containing the transaction to be forked out and becoming orphaned shortly after. This could create the opportunity to double spend, once on the mainchain and once on the sidechain, if the transaction was already added to the sidechain ledger. The binding eliminates such a situation. In case of a fork in the mainchain, the sidechain blocks that refer to the forked out mainchain block will also be reverted.

Backward Transactions and Certifiers

Now for the most interesting part. How can the mainchain verify incoming backward transactions if it doesn’t keep track of the sidechains? Using the bookkeeper analogy from before the following problem has to be solved: The mainchain bookkeepers need to add incoming transactions from the sidechains to their book, but can never look at the other books around them.

I would like to go back to the differentiating factor of sidechains and drivechains that I mentioned earlier. For a pegged sidechain construction there are two operational modes which concern the execution of backward transactions: synchronous and asynchronous.

“The synchronous mode implies that both main and sidechains are aware of each other and can verify transfer transactions directly, while the asynchronous mode relies on validators to process transfers.” - Sidechain Whitepaper; Garoffolo, Viglione

We decided on developing the SCP and CCP independently of each other. Since it is a stated goal to enable a variety of different SCP’s, it is not feasible for the mainchain to track every sidechain, for it would have to know each individual consensus protocol. This implies that strictly speaking, the proposed implementation qualifies as a drivechain rather than a sidechain, for its operational mode is asynchronous: the mainchain doesn’t keep track of the sidechains.

Getting Transaction Data from Sidechain to Mainchain

From a data point of view, to make all of this work there needs to be a transfer mechanism, initiated on the sidechain, that informs the mainchain of incoming backward transactions. This is done by introducing a new type of data container called Cross-Chain Certificates (CCCert’s).

The CCCert contains basic information, such as the sidechain identifier (SCid) and the CCCert ID as a header. The Backward Transfer List collects all cross-chain transactions. The last three data fields concern the certifiers that fulfill the role of the validators mentioned in the quote above.

The mainchain bookkeepers can’t look at the other books (sidechains) but have to know when something that relates to their book is happening. Somebody must communicate this to them in a standardized way. Certifiers are the ones to tell the mainchain bookkeepers about incoming transactions, and the standardized communication method is via the Cross-Chain Certificates.

Certifiers register on the mainchain via a special type of transaction, that includes the sidechain ID of the chain that they are registering for and a deposit that gets locked. This stake has a role in preventing fraud, but more about that in a minute. Every stakeholder on the mainchain is eligible to become a certifier. A subset of all certifiers verifies the backward transactions on the sidechain, collects them in the Backward Transfer List, signs the resulting CCCert with an aggregated signature, and sends it to the mainchain.

Facilitating backward transactions is a form of work. There needs to be an incentive to do this work. Additionally, the incentive must be designed, so that honest behavior is encouraged and malicious behavior must not be profitable. One of the main objectives was to design the protocol in a way that would decentralize the process of cross-chain verification.

Certifiers receive incentive through collecting the transaction fees of all transactions they are processing. If they submit fraudulent certificates they will not be able to unlock their stake. A group of certifiers that have a combined deposit X locked up on the mainchain is only allowed to sign a CCCert that has a combined total of 0.5X. This is called the maximum certificate amount (MAX_CERT_AMOUNT).

If the amount per certificate was not capped it would be possible to lock up a deposit, sign a fraudulent CCCert worth more than the deposit itself, sending it to a self-controlled address on the mainchain, and live happily with losing one’s stake.

Reporting Fraud

Enforcing this measure is based on the assumption of an honest majority. As you might have noticed there is a data field contained within the CCCert named Fraud Reports List. This field would be used the following way in case fraud was to occur:

- A fraudulent certificate CCCert(i) is created privately and signed by the majority of certifiers in the group(i).

- The fraudulent certificate CCCert(i) is then sent to the mainchain and included into a block(i). The mainchain is not able to verify the certificate and detect the fraud itself.

- The fraudulent certificate syncs back into the sidechain (see Full Referencing).

- The next group of certifiers(i+1) verify the previous CCCert(i) on the sidechain, detect the fraud and include a Fraud Report in their certificate CCCert(i+1).

- Once the mainchain receives CCCert(i+1) containing the fraud report, the group of malicious certifiers(i) will not be able to unlock their deposit.

- If the group(i+1) does not include a fraud report, the group after them(i+2) will and both fraudulent groups from before (i and i+1) will lose their deposit.

By not reporting a detected fraud a group would risk losing their deposit, as well as the originally malicious group. It’s also important to note that it is not possible by protocol design to have one certifier in a certifier group back-to-back.

To protect the mainchain from inflation should all else go wrong there is a last line of defense. The safeguard is a mechanism on the mainchain, which tracks the total amount of assets that have been transferred to each individual sidechain. It’s impossible to withdraw more coins from a sidechain than the amount that has been moved there in the first place, therefore preventing inflation.

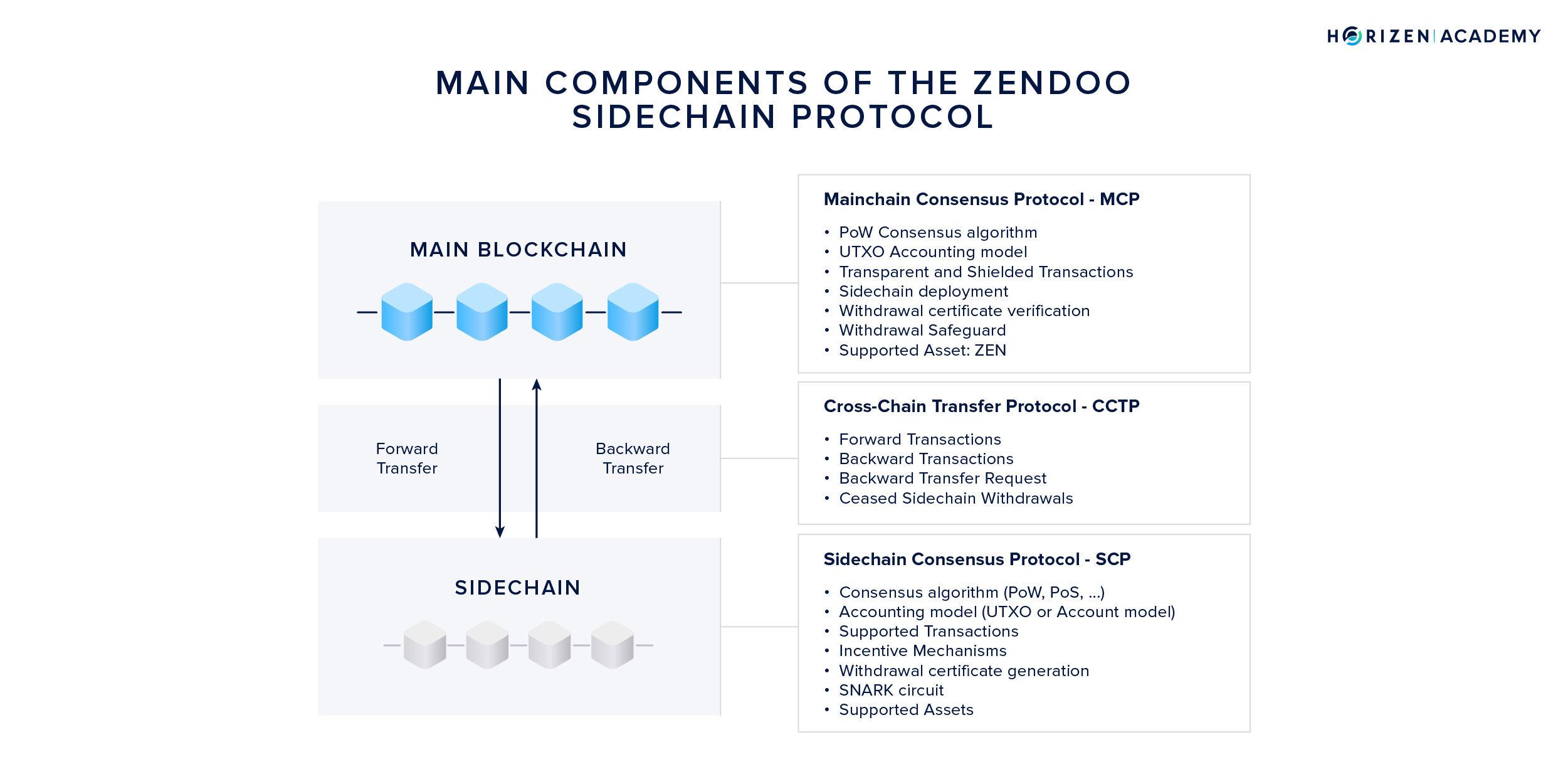

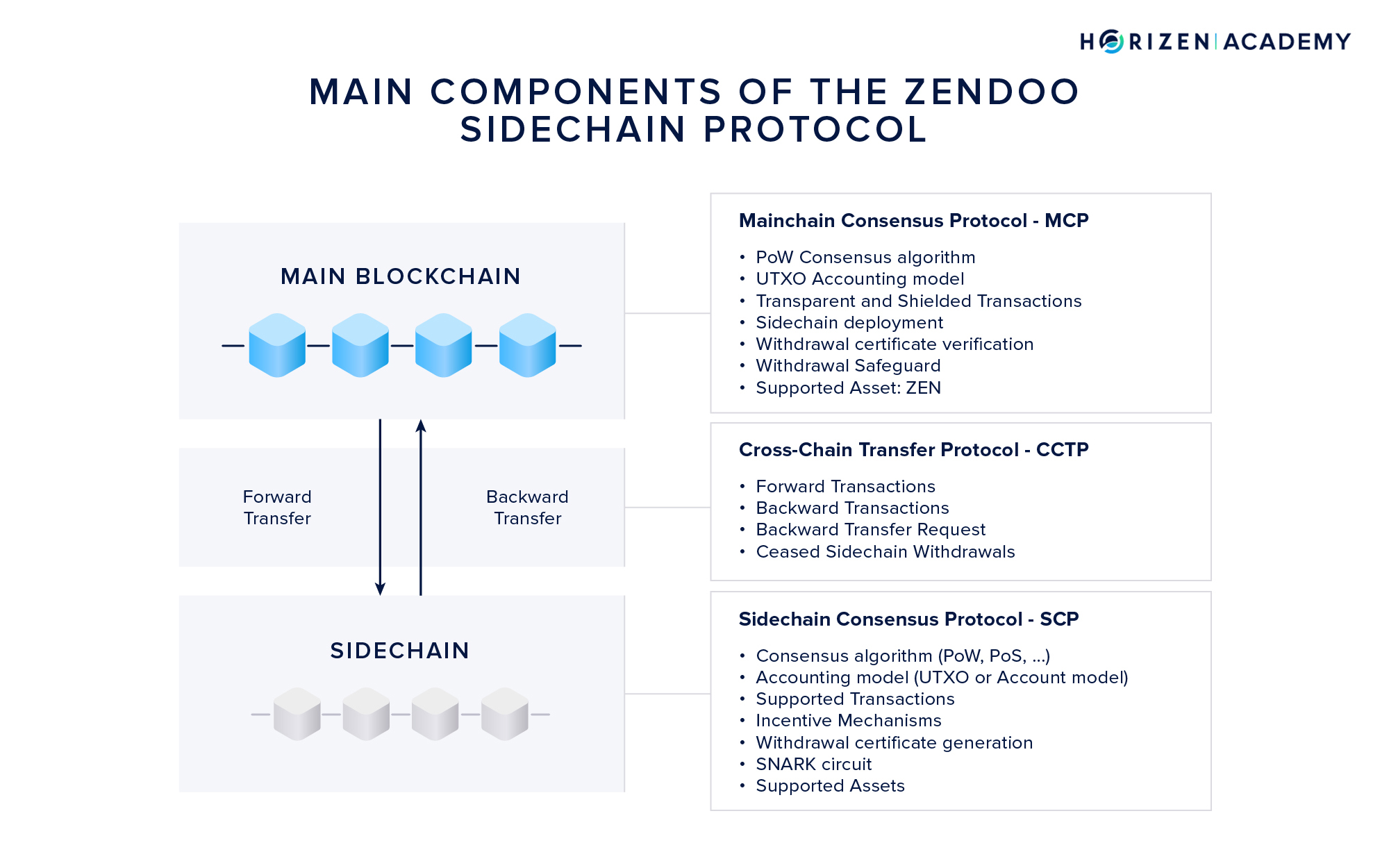

The Zendoo Protocol

Horizen’s current sidechain implementation, the Zendoo protocol was released early in 2020. It introduces:

“a standardized mechanism to register and interact with separate sidechain systems. By interaction, we mean the Cross-Chain Transfer Protocol, which enables sending a native asset to a sidechain and receiving it back in a secure and verifiable way without the mainchain knowing anything about the internal sidechain construction or operations.”

In more general terms, the Zendoo protocol allows a Bitcoin-based blockchain protocol to operate with any domain-specific blockchain or blockchain-like system. The blockchain protocol is upgraded only once to introduce the mechanism for deploying sidechains and to enable cross-chain transfers.

Zendoo allows backward transfers to be verified by the mainchain without relying on external validators or certifiers. The mainchain does not monitor sidechains (asymmetric peg) and doesn’t know anything about their internal structure. Zendoo accomplishes this by generating recursive proofs for each sidechain state transition.

Main Components in Zendoo

Most sidechain constructions consist of three elements:

- The Mainchain Consensus Protocol - MCP

- The Cross-Chain Transfer Protocol - CCTP

- The Sidechain Consensus Protocol - SCP

Depending on the sidechain structure, these components can be either highly dependent on one another or highly decoupled. The Zendoo protocol allows various degrees of freedom concerning the SCP. The Cross-Chain Transfer Protocol serves as a bridge between MCP and all sidechains.

The Mainchain Consensus Protocol - MCP

Horizen’s mainchain consensus protocol comprises the Proof of Work and Nakamoto consensus algorithm, the UTXO accounting model, and the transaction logic. The Zendoo specific parts of the MCP are the deployment of new sidechains via special bootstrapping transactions, a new transaction type to transfer assets to a sidechain as well as the verification of incoming backward transfers from sidechains.

The Cross-Chain Transfer Protocol - CCTP

The Cross-Chain Transfer Protocol is the bridge between main and sidechain, and is unified and fixed by the mainchain consensus protocol. Its two main components are forward and backward transfers. In forward transfers, ZEN is sent from the mainchain to a sidechain. In backward transfers, ZEN is returned to the mainchain.

Because sidechains monitor the mainchain, they can verify forward transfers themselves. Since the mainchain doesn’t monitor sidechains, Zendoo introduces a mechanism capable of verifying backward transfers without relying on certifiers.

A vital component of the Cross-Chain Transfer Protocol is the Withdrawal Certificate. This certificate groups all of the backward transfers from a sidechain within a given time period - the Withdrawal Epoch - and broadcasts them to the mainchain. Every sidechain needs a mechanism to generate valid withdrawal certificates. Each sidechain also needs to define a proof system so the mainchain can verify incoming backward transfers. We’ll get to proof systems shortly.

The Sidechain Consensus Protocol - SCP

The sidechain consensus protocol includes all parameters of the sidechain. Typically, the consensus algorithm would describe the mechanism to agree on a single version of history.

A sidechain in Zendoo can run a different consensus mechanism, accounting model or data structure than the mainchain. The sidechain doesn’t even have to be a blockchain at all, as long as it adheres to the cross-chain transfer protocol, it will be able to communicate with the main blockchain.

A Horizen-compatible sidechain allows for great freedom. As a first step, Horizen provides a reference implementation for a sidechain consensus protocol named Latus, based on a delegated Proof of Stake consensus mechanism inspired by Ouroboros Praos. A detailed description of the Latus construction is out of scope for this article. We refer the interested reader to our Zendoo paper to learn more.

Modifications of the Mainchain Protocol

Some modifications to the mainchain protocol are necessary to allow the deployment and use of sidechains on a Bitcoin-based blockchain.

- First, and most importantly, a select type of bootstrapping transaction is introduced to deploy sidechains.

- Second, a mechanism to process and verify incoming Withdrawal Certificates is needed.

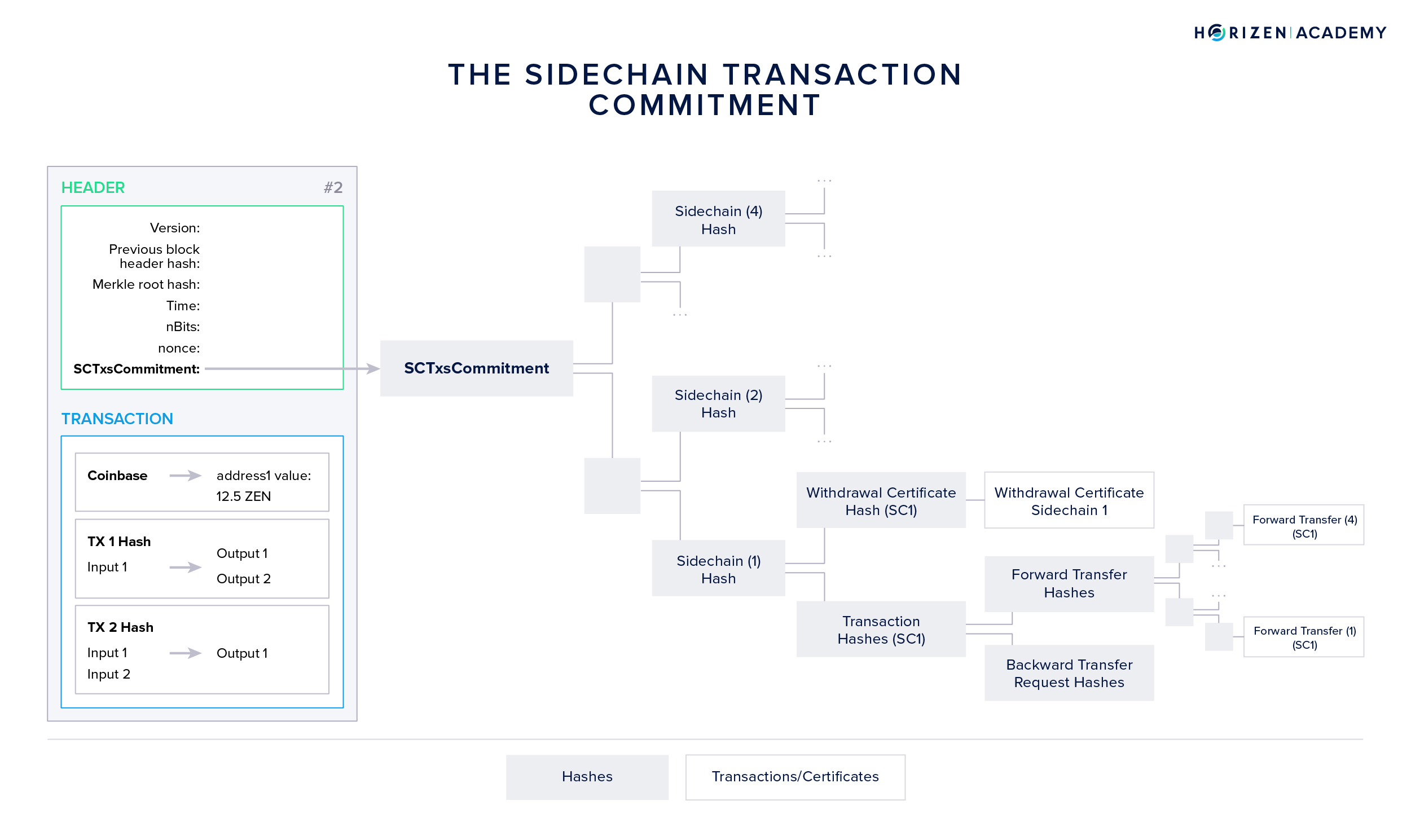

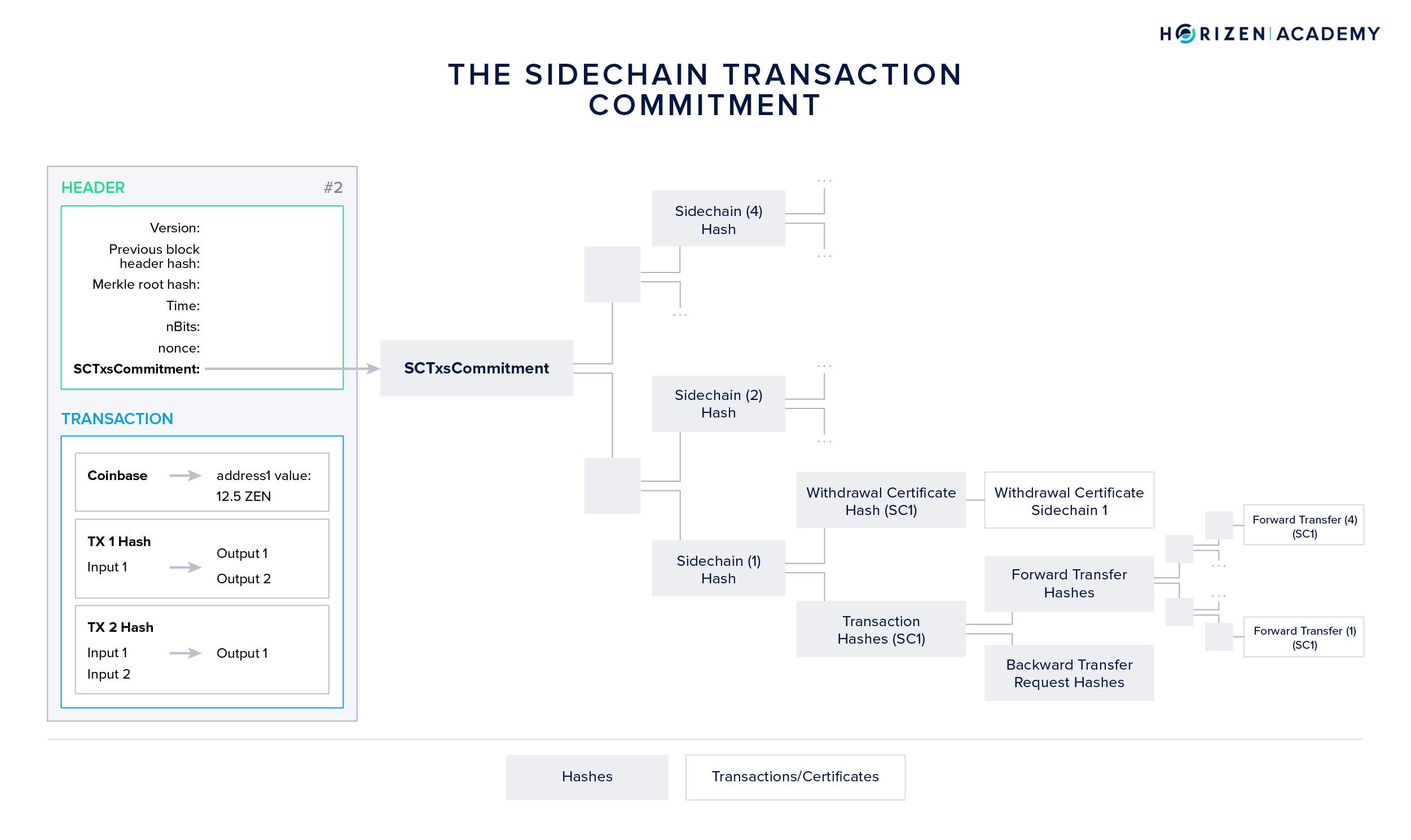

- Third, a new data field, the Sidechain Transaction Commitment is added to the mainchain block header, where a Merkle root of all sidechain related transactions is recorded.

- Lastly, a withdrawal safeguard is introduced as a mechanism to prevent unforeseen inflation of the coin supply.

In the following sections we will go through the mainchain modifications that allow deploying and using sidechains.

Understanding how the mainchain verifies incoming sidechain transactions without directly tracking them is crucial for understanding all other mainchain protocol changes; hence we will look at this mechanism first.

Verification of Backward Transfers

Most sidechain protocols rely on certifiers acting as a bridge between chains. These entities monitor one or more sidechains, collect and verify backward transactions, and broadcast them on the mainchain. Certifiers can either be a trusted group of centralized actors, or a decentralized group of network participants incentivized to follow the protocol. While we assume an honest majority among verifiers, there is still the possibility of malicious activity.

Ideally, backward transfers are objectively verifiable without the need to rely on intermediaries. This need to remove intermediaries is Horizen’s motivation for building a backward transfer mechanism that relies on a proof system rather than software instances run by human entities.

Proof Systems

On the highest level, a proof system allows a prover to prove to a validator that a given statement is true. Instead of the validator redoing the entire computation to verify the result, the prover can generate a proof for its correctness. A proof comprises a set of values that the verifier uses to compute a binary output - true or false. When the verification function returns true the computation was performed correctly, if it returns false, it wasn’t.

Verifying state transitions in a system is one great use case for a proof system. A blockchain is a state machine in the sense that every block records new transactions onto the ledger, changing the state of the system. Nodes verify each block before they add it to their version of the ledger. They check if transactions have valid digital signatures attached, if only previously unspent transaction outputs are spent, and if the Proof of Work attached to the block meets the current difficulty. With a proof system, a miner could generate a proof that the state transition (new block) was performed according to the protocol. All other nodes would simply have to verify if the proof is correct and could save themselves from verifying each part of the block individually.

Zero-Knowledge proofs such as zkSNARKs are best known for their application in privacy-preserving cryptocurrencies. Horizen, Zcash and other protocols utilize zkSNARKs to enable the private transfer of money. When proofs are used to transfer money privately, a user creates a transaction according to the blockchain’s protocol.

Instead of broadcasting this transaction in plaintext to the network, the user generates a proof that the transaction is valid and broadcasts this proof. The proof entails all necessary information about the transaction: the previously unspent inputs and the digital signature(s) satisfying the spending conditions of the inputs.

Once broadcast, nodes will verify the proof instead of the plaintext transaction. For this to work, an essential property of the proof system comes down to soundness and completeness.

- Soundness means a proof can practically not be faked.

- Completeness means that a valid proof always evaluates to true when verified.

While completeness can be mathematically guaranteed, soundness is practically guaranteed, as no entity has infinite, in the literal sense, computational resources.

In Zendoo, sidechains generate proofs of their state transitions. When a withdrawal certificate is submitted to the mainchain, a proof of correct state transitions is attached. Miners on the mainchain verify this proof before including the withdrawal certificate in a mainchain block. This is how an algorithm replaces certifiers. But how exactly are proofs for state transitions generated? Recursively!

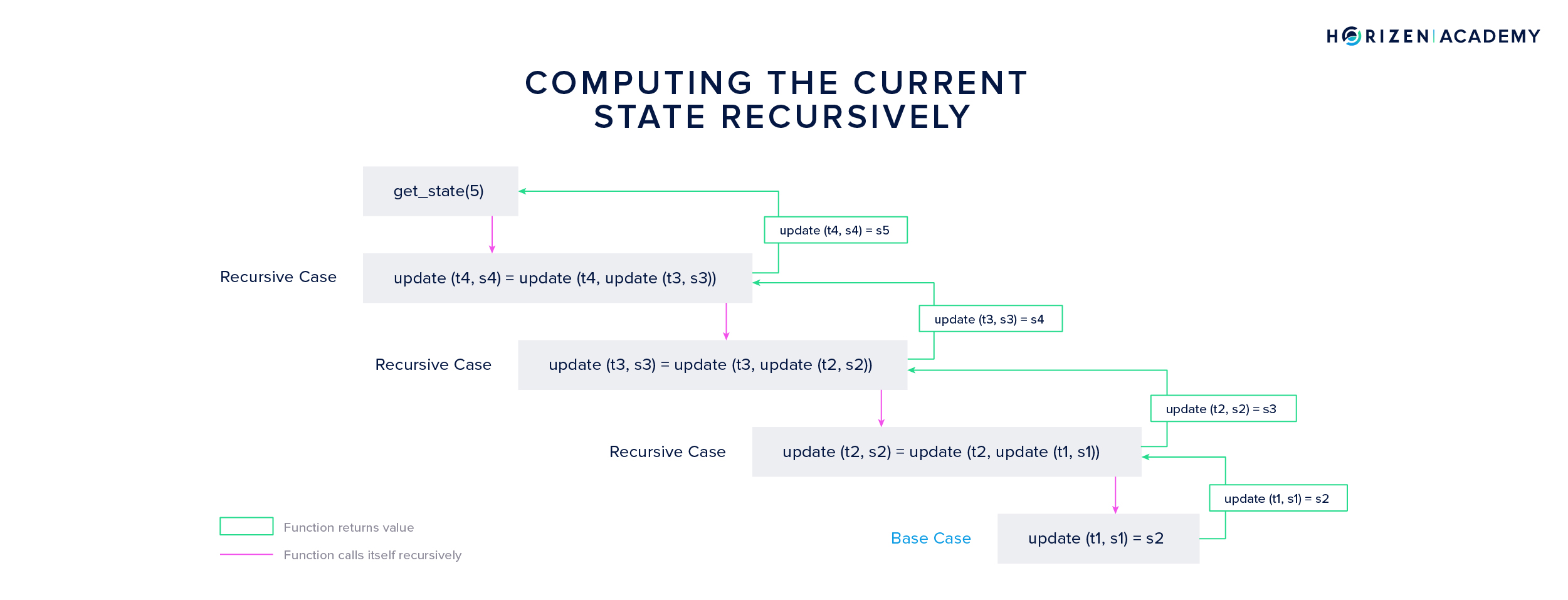

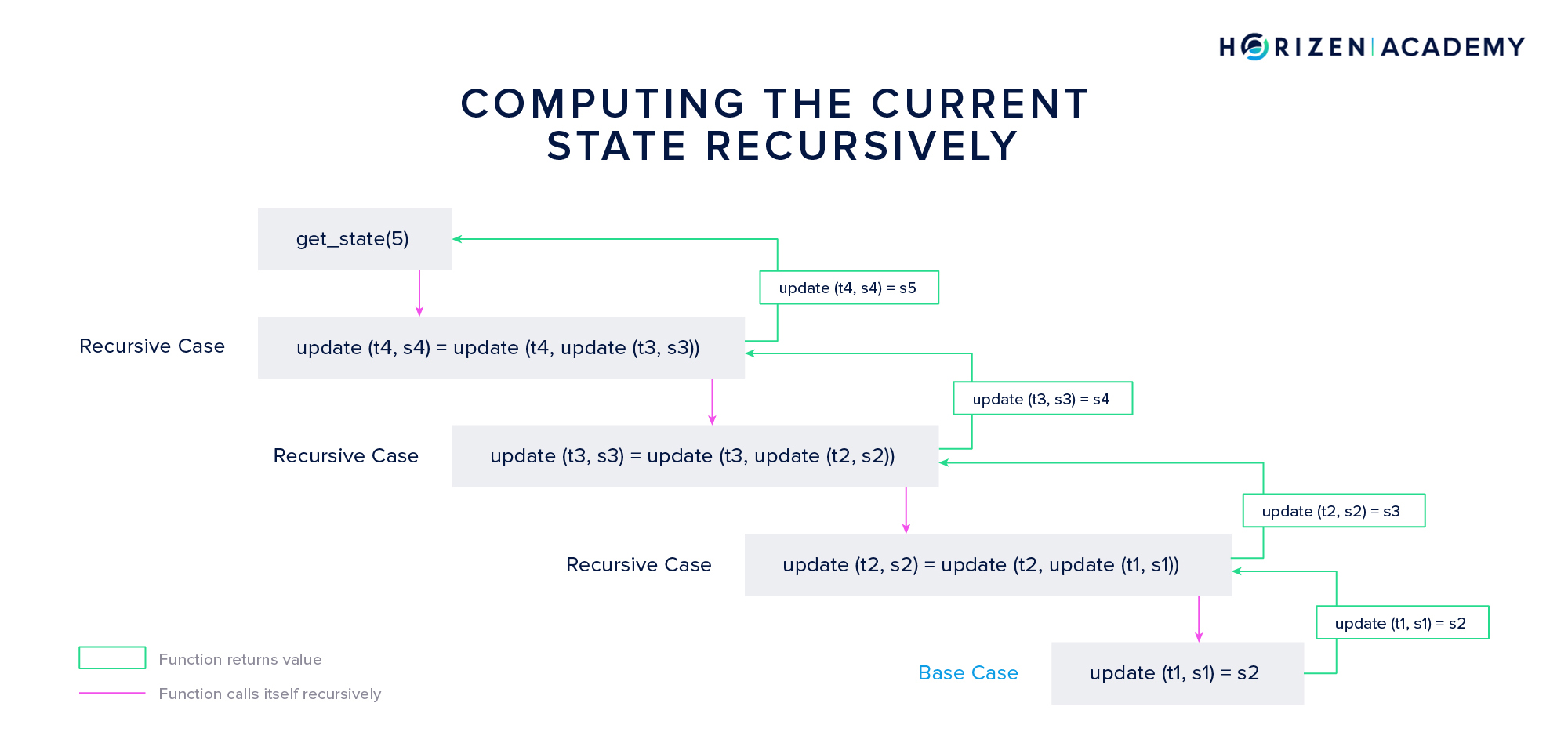

Recursion

To understand the generation of state transition proofs, we need to understand the concept of recursion. Recursion is not only useful for understanding the sidechain design, but also an important concept in general computer science.

Recursion in terms of computer science, is a procedure of solving a problem where the solution depends on solutions to smaller instances of the same problem.

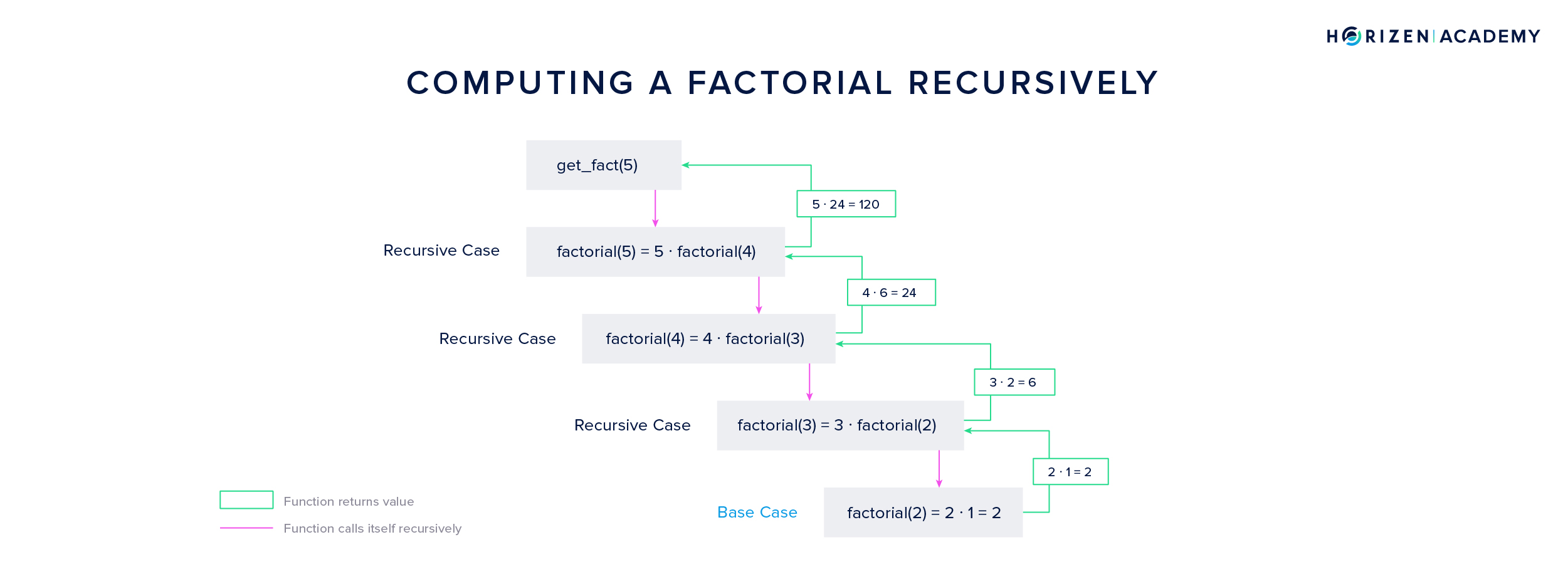

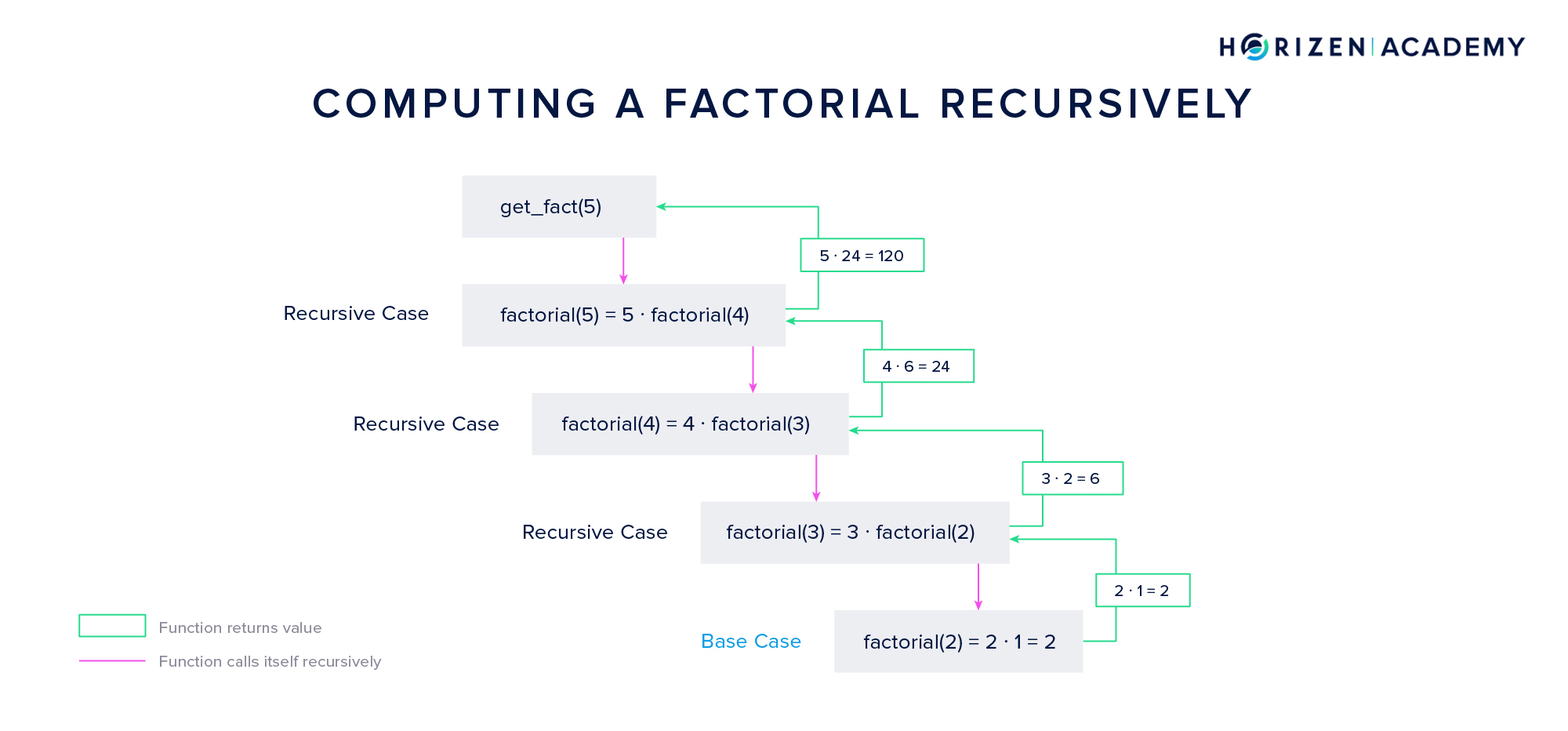

Solving a problem recursively means that the function solving the problem can call itself. This is best illustrated in an example. The most common and intuitive example is calculating the factorial of a given number. A general expression for the factorial of a number is:

\[n! = n \cdot (n-1) \cdot (n-2) \cdot ... \cdot 1\]Hence, the factorial of 5 is

\[5! = 5 \cdot 4 \cdot 3 \cdot 2 \cdot 1 = 120\]Writing a function that calculates the factorial of a given number is elegantly achieved using recursion. The idea is that the factorial of the number 5 is equal to five times the factorial of the number four:

\(5! = 5 \cdot 4!\)

The solution to the problem 5! then depends on a smaller instance of the same problem: 4!.

In the example above, the recursive function starts with the first recursive case \(5! = 5 \cdot 4!\), then starts another instance of the function that computes 4! - and so on. This continues until the base case is reached. The base case is the factorial of the number 2, which equals 2.

Instances of the function are closed subsequently after returning their result to the function’s next highest instance. In the example above, the base case returns 2 to the next highest instance, which will use the result to compute 3!, and so on. In the last step, 120 is returned, and the highest instance of the function is closed.

In C, the function calculating the factorial can be elegantly written. You can see below that the function factorial is used within the function itself (factorial(n-1)). Even without a basic understanding of software development, you might appreciate the simplicity. We can compute the factorial for any given number in just four lines of code.

long factorial(int n)

{

if (n == 0) //Base Case

return 1;

else //Recursive Case(s)

return (n*factorial(n-1));

}

Note: In the graphic before we called \(2 \cdot 1\) the base case for simplicity’s sake.

We want to achieve a proof of state transitions in the context of our sidechains. If the state transition is proven, the resulting state and hence all backward transfers are automatically proven. But how does recursion apply to this?

State Transition Proofs

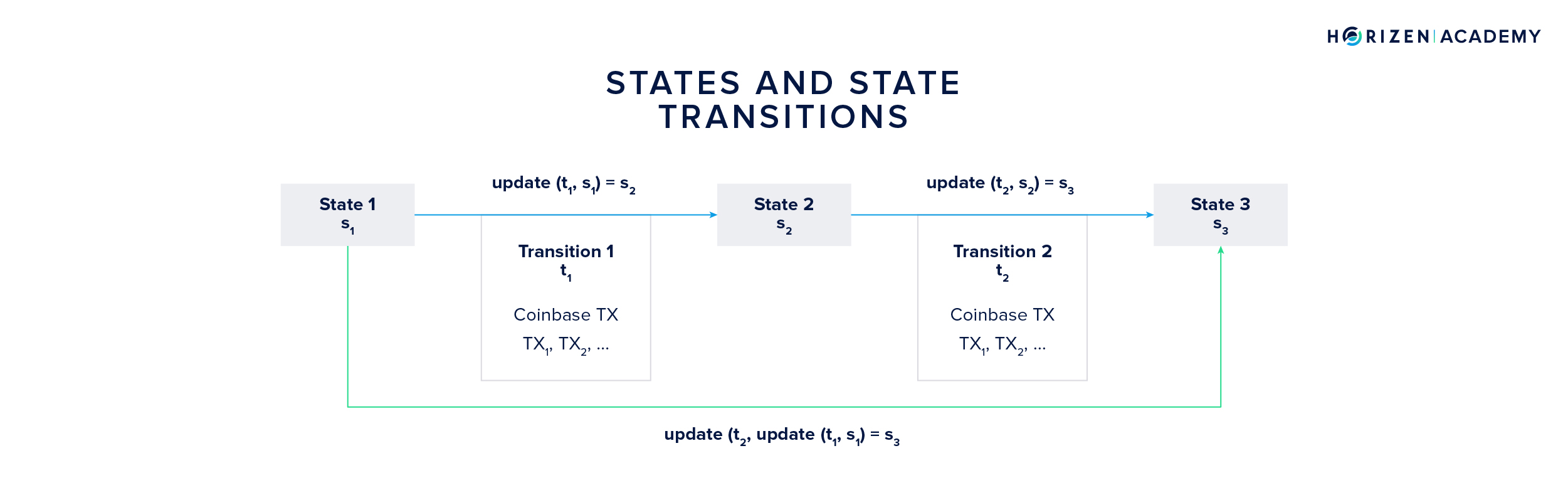

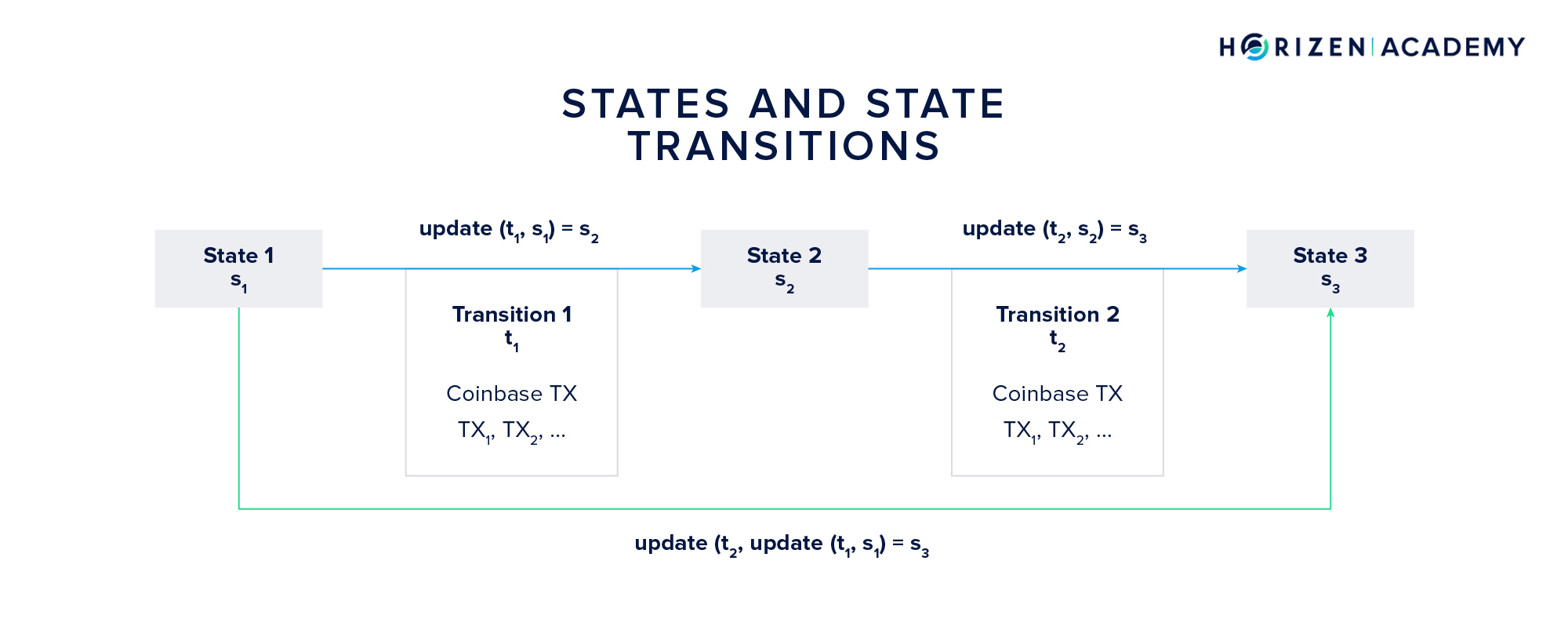

The blockchain’s state transition logic is a function that takes the current state \(s*i\) and the most recent set of transactions \(t_i\) as an input, and returns the next state \(s*{i+1}\) as an output. The factorial of five is expressed as the number five times the result of the function for computing the factorial of four. The current state can also be computed based on the current transition and the result of the function for computing the last state. Let us look at a tangible example.

Let’s assume a sidechain starts in state 1 \(s_1\) with its genesis block. The first transition \(t_1\) consists of all transactions included in the first “real” block applied to the first state. The transition function, let’s call it update, takes these two parameters, the initial state (Genesis Block) and the first transition (read: transactions), and computes the next state \(s_2\), given the inputs constitute valid arguments to the update function.

The same logic applies for the second state transition. Based on state \(s_2\) and the second transition \(t_2\) the update function computes the third state \(s_3\).

Now, the current state of the sidechain can always be computed from the initial state \(s_1\) and all transitions \(t_i\) the system underwent. It allows one to subsequently compute every state the system went through. In our example, the third state \(s_3\) can be computed as:

\[s_3 = update(t_2, update(t_1, s_1)).\]We simply replaced \(s_2\) from the second formula in this section with the right term of the first equation.

Recursive State Transition Proofs

The construction shown above follows the same pattern we discussed when calculating the factorial. Do you recognize the recursive pattern? The function update calls itself subsequently and opens new instances of the same function until the base case is reached.

The base case here is the first state transition resulting in state \(s_2\). Once this base case is reached, the different instances of the update function return their result to the next highest instance of the same function until finally, the current state is returned and all instances of the function are closed.

A general mathematical expression for this is

\[s_{n+1} = update(t_{n}, s_{n}) = update(t_{n}, update (t_{n-1}, s_{n-1})\]This construction is of great value for verifiable sidechains. Not only can states be computed recursively, but so can proofs for each state and state transition. What is needed for the Zendoo protocol is a proof of the statement:

There was a series of state transitions \((t*1, …, t_n)\) and by applying these state transitions to the initial state \(s_1\) one after another the state \((s{n+1}))\ is reached.

We now understand how to compute states recursively. But why do we want to compute a proof for each of those transitions? Remember that the mainchain does not monitor the different sidechains and verify the state transitions.

To avoid monitoring all of the sidechains, we can verify a proof submitted with each incoming withdrawal certificate. When validated, this proof will return true if the sidechain operated as intended, and false if it didn’t. The mainchain accepts backward transfers included in a withdrawal certificate if, and only if the attached proof evaluates to true.

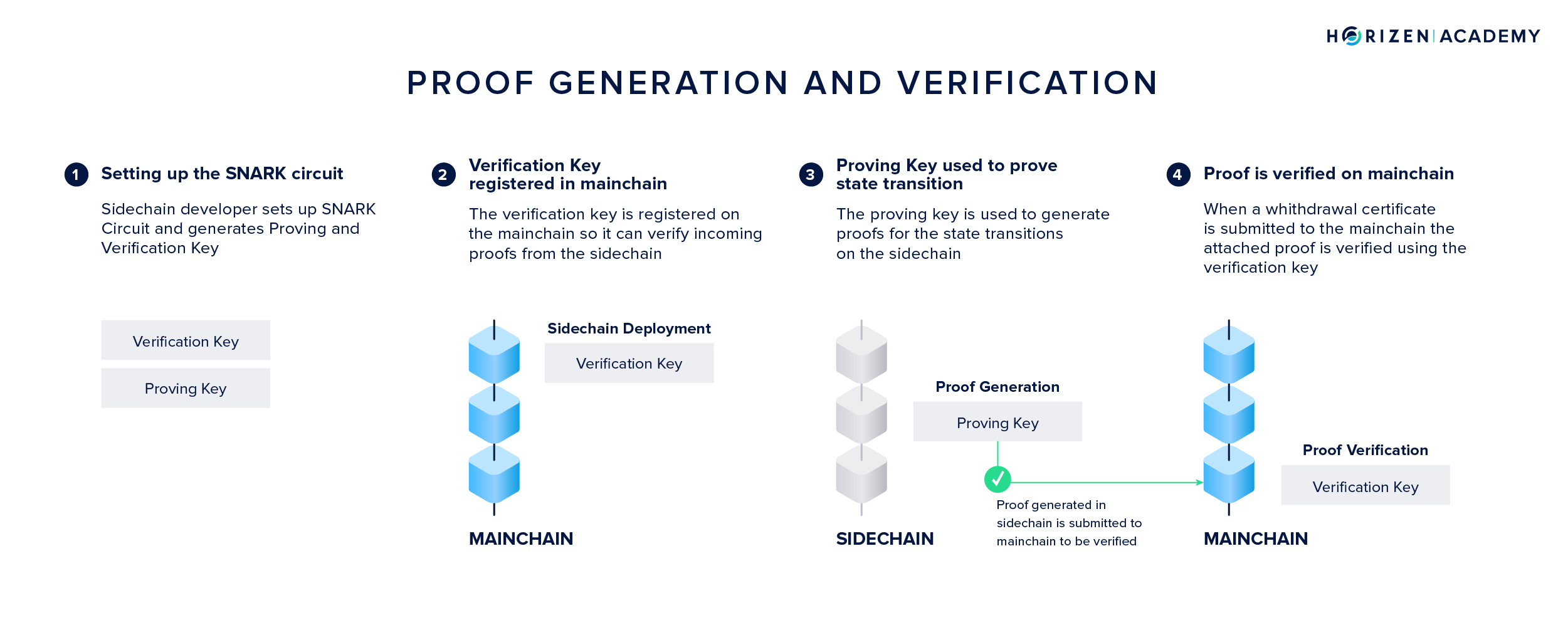

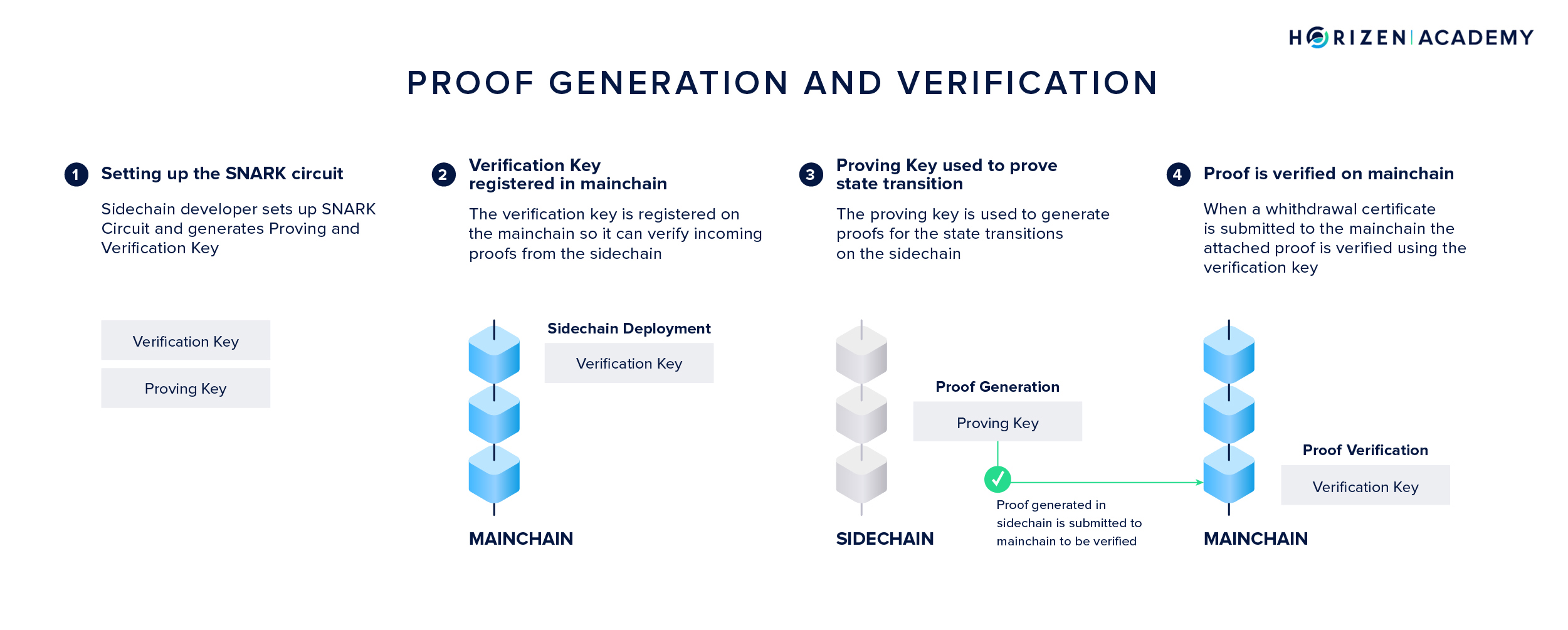

Using SNARKS - Succinct Non-Interactive Arguments of Knowledge

So how does generating a proof work exactly for a given sidechain? First, there exists a wide range of proof systems. The proof system used for the Zendoo sidechain construction is a SNARK proof system - an acronym for Succinct Non-Interactive Arguments of Knowledge. Let’s dive deeper:

- Succinct refers to the proofs being “short” in the sense of computationally inexpensive to generate and verify.

- Non-interactive means that the prover and verifier don’t have to be online at the same time. With non-interactive proofs, the prover can construct the proof without the need for communication with the verifier. This proof can be recorded on the blockchain to be verified at any time.

- Arguments of Knowledge describes the proof being computationally sound, i.e. no adversary can construct a false proof even with access to huge computational resources.

With SNARKs we can produce proofs of constant size for almost any type of computation. A SNARK proving system comprises a triplet of algorithms: Setup, Prove, and Verify.

When a SNARK system is setup, a proving key \(pk\) and a verification key \(vk\) are generated for the system C. The verification key is registered on the mainchain at the time of sidechain deployment.

\[(pk, vk) \leftarrow Setup(C)\]To prove a computation was performed correctly (or, in more general terms, a statement) a proof \(\pi\) is generated. Generating a proof for the correct state transition \(t\) from state \(s_1\) to the final state \(s_n\) happens based on four inputs:

- the proving key \(pk\)

- the initial state \(s_1\)

- the transition \(t\)

- and the resulting state \(s_n\)

Just like we computed states recursively, we can compute proofs recursively. The logic is exactly the same: Starting from a base case (the first state transition) proofs are sequentially merged until a single proof for the state in question remains.

This proof is now broadcast on the mainchain where it is verified. Verifying a proof of state n \(s_n\) happens based on four inputs:

- the verification key \(vk\)

- the initial state \(s_1\)

- the final state \(s_n\)

- and the proof \(\pi\)

Proofs for the correct execution of the sidechain logic are generated periodically, one for every withdrawal epoch. Only the proof and the final state have to be transmitted to the main blockchain. The initial state can be taken from the bootstrapping transaction or the most recent withdrawal certificate. The verification key resides on the mainchain since deployment. It’s important to note that proof generation doesn’t have to happen in a trustless environment. A sidechain might just as well use a Proof of Authority scheme where a group of trusted certifiers generates proofs.

Now that there is a basic understanding of what proof systems are, how recursion works, and how it is applied to generate proofs for any state (block) of the sidechain and in turn all withdrawals, we continue by looking at the remaining modifications to the mainchain needed to enable sidechains.

SNARK Usage in Latus Sidechain

It is ultimately up to a sidechain developer to decide how proofs of state transitions are constructed. In Horizen’s reference sidechain implementation, the Latus sidechain, proofs are first generated for individual transactions. These proofs are then merged pairwise to get a proof for the entire block. Another sidechain implementation might merge them sequentially like in the example used above. The developer can choose their preferred method.

Once a withdrawal epoch has ended, the proofs for all blocks contained in that epoch are merged. This yields a proof of the entire epoch and all transactions within it. This withdrawal epoch proof is used to generate a final proof attached to the epoch’s withdrawal certificate. This final proof legitimizes all backward transfers to the mainchain, proves all mainchain blocks were referenced, and all forward transfers were included.

The entire process of key and proof generation, as well as proof verification, is quite sophisticated. Some mechanisms described herein are simplified to convey the concept to a wider audience.

Sidechains Transactions Commitment

The structure of the mainchain block headers was upgraded and a new data field, the Sidechain Transactions Commitment (SCTxsCommitment) was introduced. The SCTxsCommitment is basically a Merkle root of an additional Merkle tree. Besides the regular Merkle root included in a block header serving as a summary of all transactions, this second Merkle tree comprises all sidechain-related transactions, namely:

- Forward Transfers (FTs) sending assets from main- to sidechain

- Withdrawal Certificates (WCerts) communicating Backward Transfers to the mainchain

- Backward Transfer Requests (BTRs) initiating Backward Transfers from within the mainchain

- Ceased Sidechain Withdrawals (CSW) allowing a user to withdraw assets from a sidechain which has become inactive

All these sidechain-related events are placed into a Merkle tree, grouped by sidechain identifiers into different branches. The resulting Merkle tree root is placed in the mainchain block header as the sidechain transactions commitment.

Including this data in the block header allows sidechain nodes to easily synchronize and verify sidechain related transactions (sidechains DO monitor the mainchain) without the need to transmit the entire mainchain block. Furthermore, it allows the construction of a SNARK, proving that all sidechain-related transactions of a given mainchain block have been processed correctly.

Withdrawal Safeguard

Uncontrolled inflation of the monetary supply is one of the most devastating bugs a blockchain can suffer from. One has to consider an event where a malfunctioning sidechain is trying to transfer more assets to the mainchain than it initially received. This could be malicious intent or simply an honest mistake.

Horizen implemented a withdrawal safeguard to prevent this. The mainchain keeps track of how much money was transferred to a given sidechain, and will only accept incoming backward transfers up to that amount. This way uncontrolled inflation becomes impossible.

Sidechain Deployment

A new sidechain in Zendoo needs to register with the mainchain using a special type of transaction called a bootstrapping transaction. Any user can build a new sidechain and submit a bootstrapping transaction wherein several essential parameters are defined.

First, a unique identifier, the ledgerId for the sidechain is defined in the bootstrapping transaction. Next, it is defined from which mainchain block onward the sidechain will become active.

A number of cryptographic keys are proclaimed for each sidechain, namely the verification keys needed to verify proofs generated on the sidechain. There is a verification key \(vk*{WCert}\) for withdrawal certificate proofs, a verification key \(vk*{BTR}\) for Backward Transfer Request proofs and a verification key \(vk_{CSW}\) for Ceased Sidechain Withdrawal proofs.

Lastly, it is defined how the proof data will be provided from the sidechain to the mainchain (number and types of included data elements).

Summary

Sidechains can be an elegant way to overcome current limitations regarding scalability and governance in the blockchain ecosystem. While you can increase the throughput, the number of transactions per second (TPS), with sidechains, they also allow experimentation without compromising the security of the main chain.

The ability to deploy sidechains will dramatically enhance the possibilities of building on top of existing public blockchains. Sidechains allow the deployment of new experimental features without having to achieve consensus among all network participants. They also keep the codebase manageable and allow developers to spin up new ledger systems with instant access to a token of established value.

One of the first use cases of a sidechain for the Horizen project will likely be the Treasury, moving the organization a step closer to becoming a decentralized autonomous organization (DAO). The main contribution of our team is providing a new backward transfer protocol that does not rely on a centralized group of validators. Every stakeholder is eligible to become a certifier if he likes to, introducing decentralization to the process of cross-chain verification.

From a security perspective, the most important thing is to design the implementation in a way that no sidechain can possibly harm the mainchain.

The SCP must have a guaranteed truly random assignment of slot leaders. Additionally liveness and persistence must be guaranteed.

The CCT security is enforced by adding references to the mainchain with every block (full referencing), introducing a cap on the total amount a group of certifiers can sign for (MAX_CERT_AMOUNT) and the safeguard tracking the total amount that has been transferred to a given sidechain and can be withdrawn.

Several sidechain implementations exist, some of them closer to production than others. A common shortcoming is that these constructions oftentimes either rely on the mainchain keeping track of sidechains, or they require some sort of certifiers to process backward transfers from side to mainchain. The Zendoo protocol allows an asymmetric sidechain construction where the mainchain doesn’t monitor sidechains but can rely on objectively verifiable proofs to validate Backward Transfers.

Zendoo comprises three main elements: The mainchain consensus protocol, the sidechain consensus protocol for which the Latus reference implementation is provided, and the cross-chain transfer protocol. MCP and CCTP are fixed, while there are many degrees of freedom with regards to the SCP.

Next, we looked at the necessary modifications to Horizen’s mainchain protocol that allow the deployment of sidechains. To understand the recursive proof system that allows the verification of backward transfers without certifiers, we introduced proof systems in general. We showed how recursion could be used to elegantly solve mathematical problems such as computing the factorial of a number and how the same concept is useful for computing state transitions and proofs.

Another modification to the mainchain is the addition of the sidechain transactions commitment (SCTxsCommitment) serving as a summary of all sidechain related transactions on the mainchain in the form of a Merkle tree. The withdrawal safeguard protects against unintended inflation originating from a buggy or malicious sidechain. Lastly, a special type of bootstrapping transaction is introduced to allow the permissionless deployment of a sidechain.