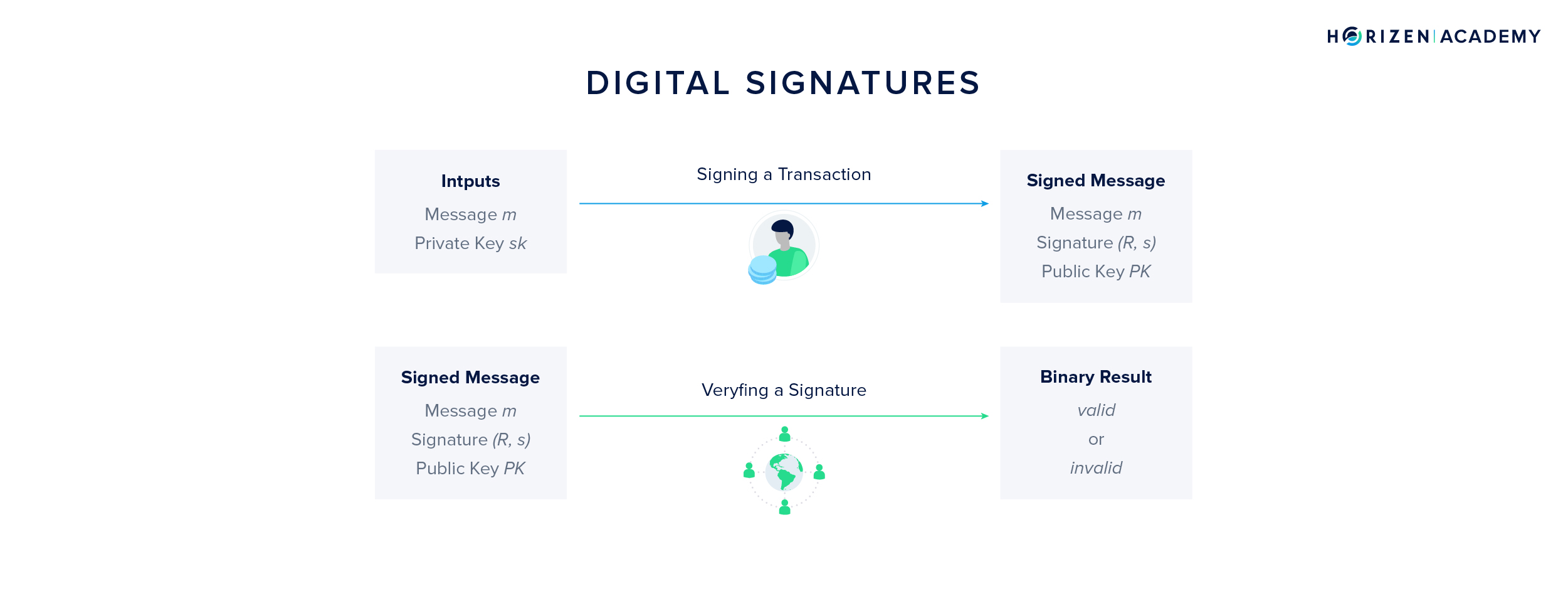

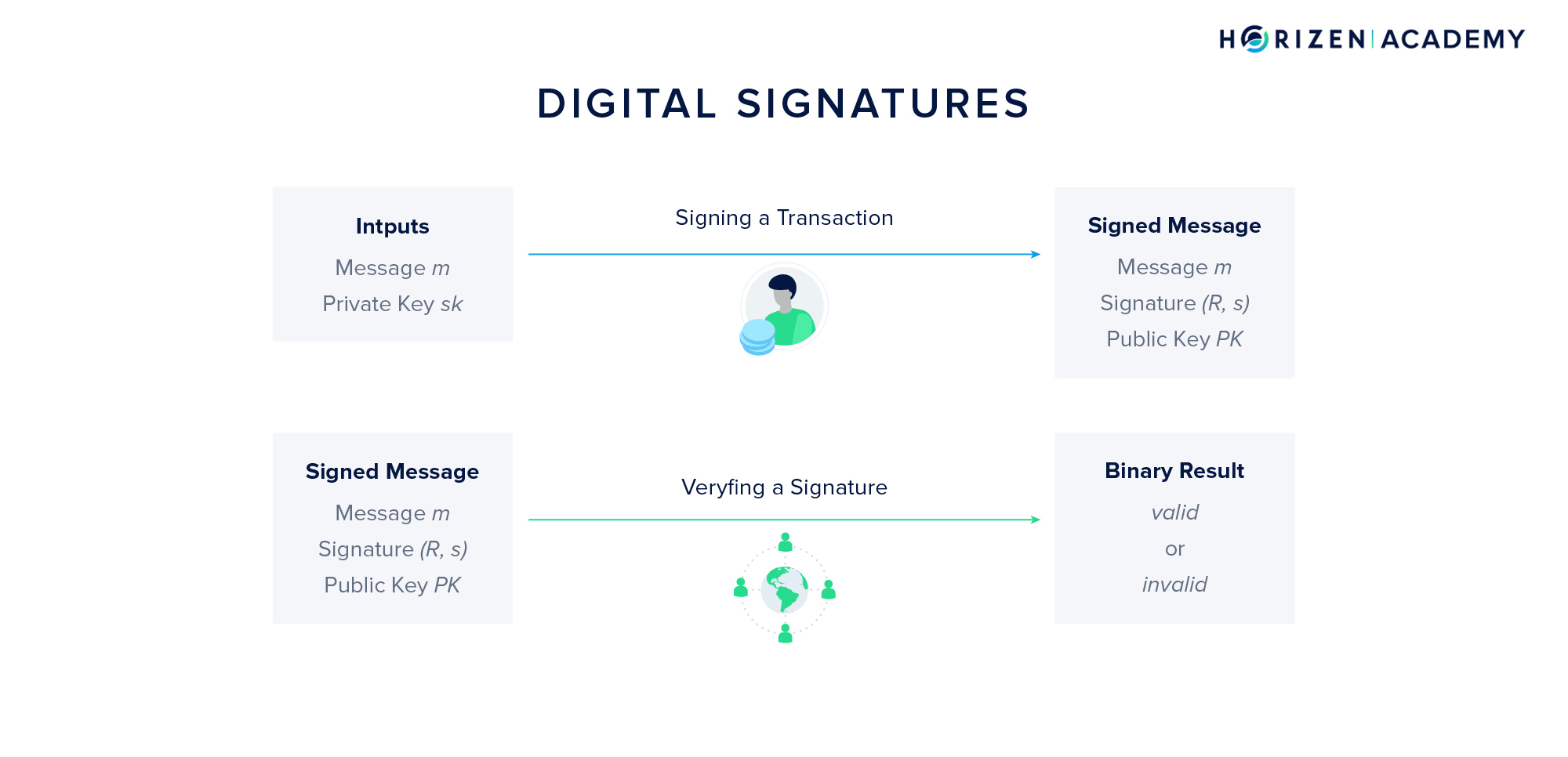

Public-Key Cryptography is used to verify ownership on a blockchain. Digital signatures allow you to prove your knowledge of a private key corresponding to a particular address without revealing any information about it.

To create a digital signature you need two components, a message, in most cases a transaction, and the private key. A verifier will use the message, the public key, and the digital signature as an input to the verification algorithm. This algorithm will then produce a binary output: Either the signature is valid, or it is not. Every full node and miner on the network will verify every single transaction using this concept.

This mechanism is usually treated as a blackbox, but we will dissect the inner workings of this cryptographic method in this article.

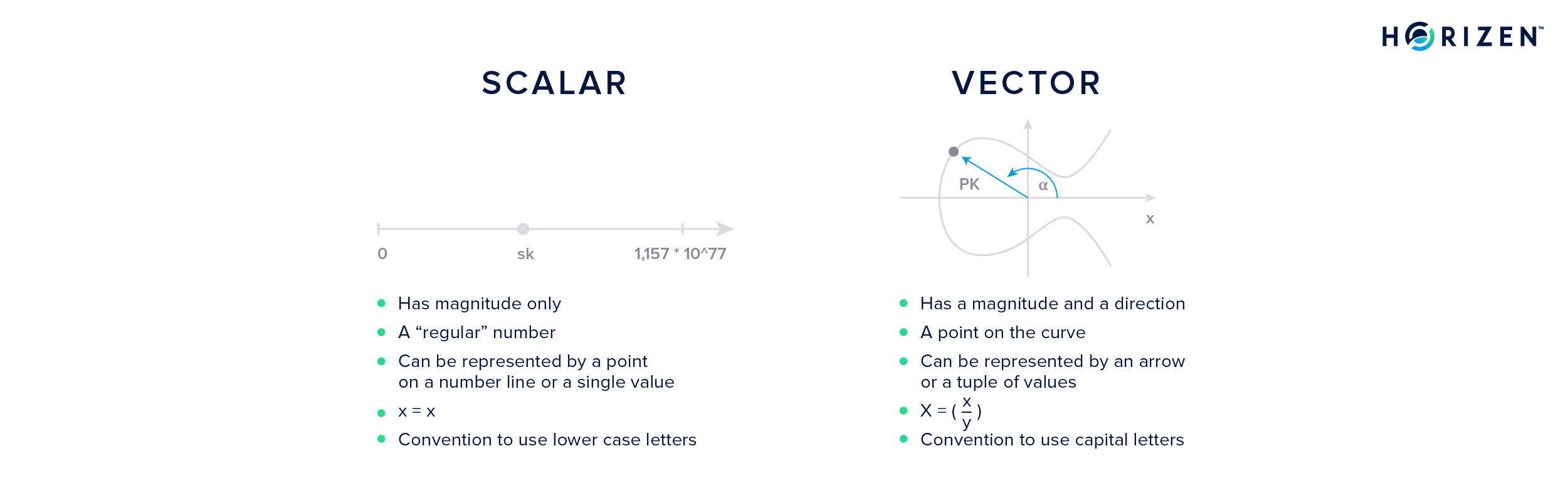

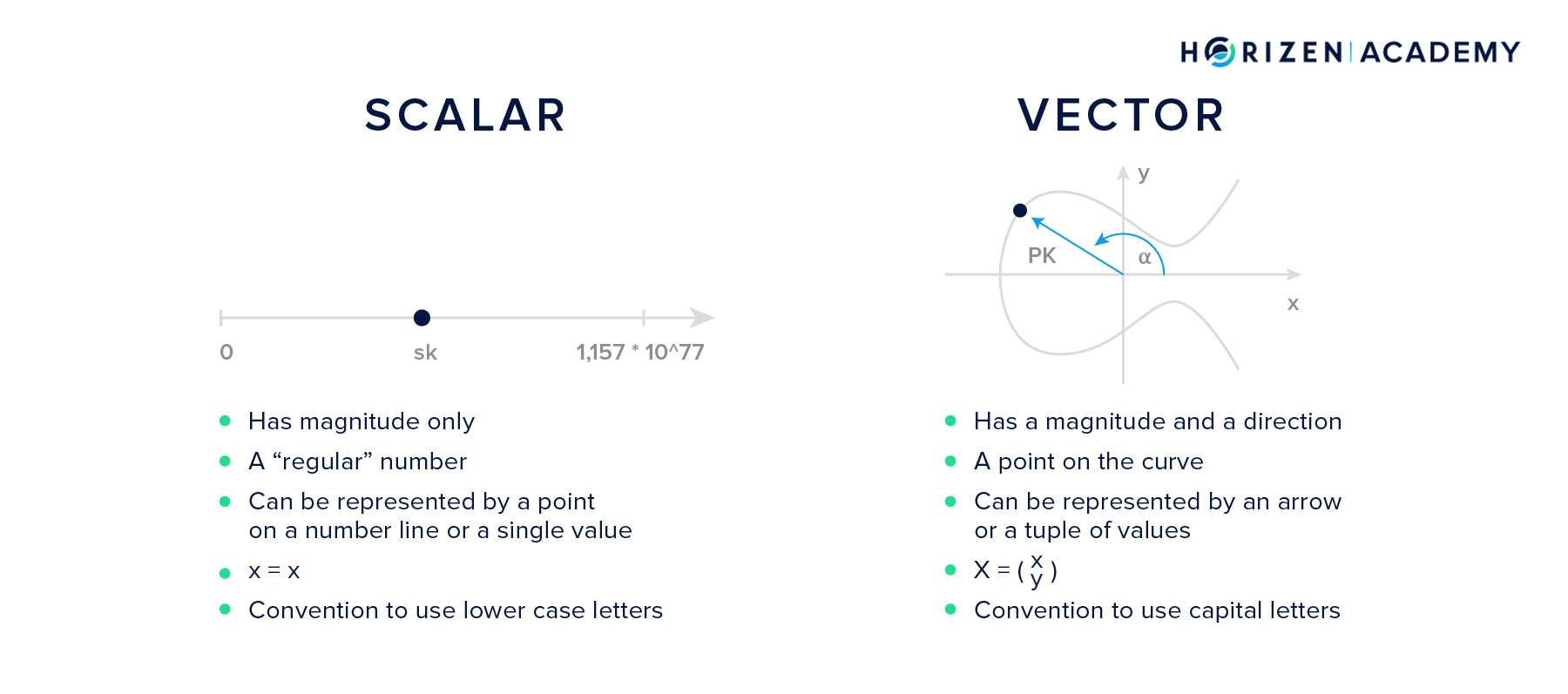

Scalars and Vectors

A scalar is something that only has a magnitude. Simply speaking, any number is a scalar. A vector, however, has a magnitude and a direction and is represented by a tuple of values. If we are looking at a two-dimensional plane, a vector can be interpreted as an arrow with a certain length, magnitude, and the angle \(\alpha\) relative to the positive x-axis, direction.

This means it is a tuple comprising two values, a double. In order to represent a vector in three dimensional space, one would use a triple of values. One value for the magnitude and two for the direction, the angle relative to x- and z-axis. Alternatively, you can use the x, y, and z- coordinates to represent a given point in three-dimensional space. Either way, you need three values.

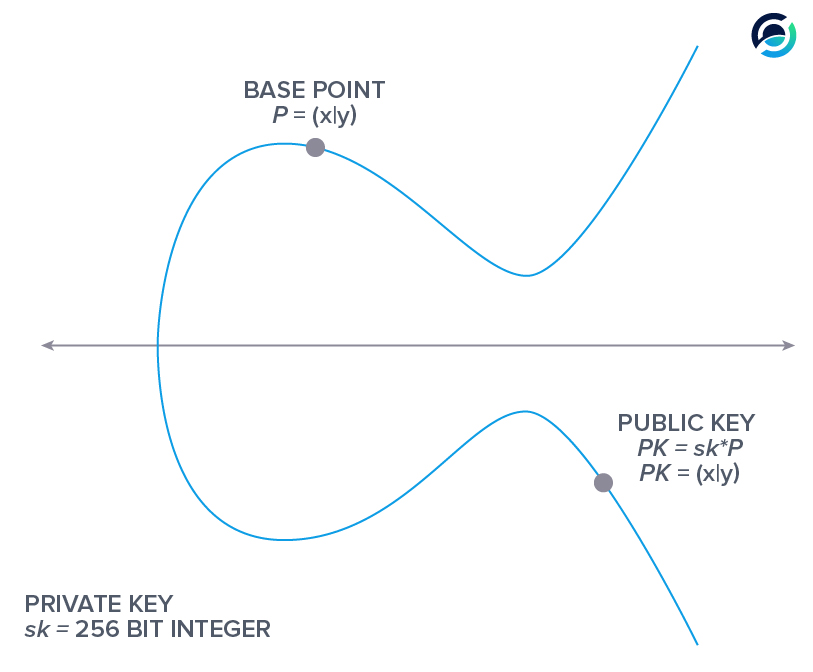

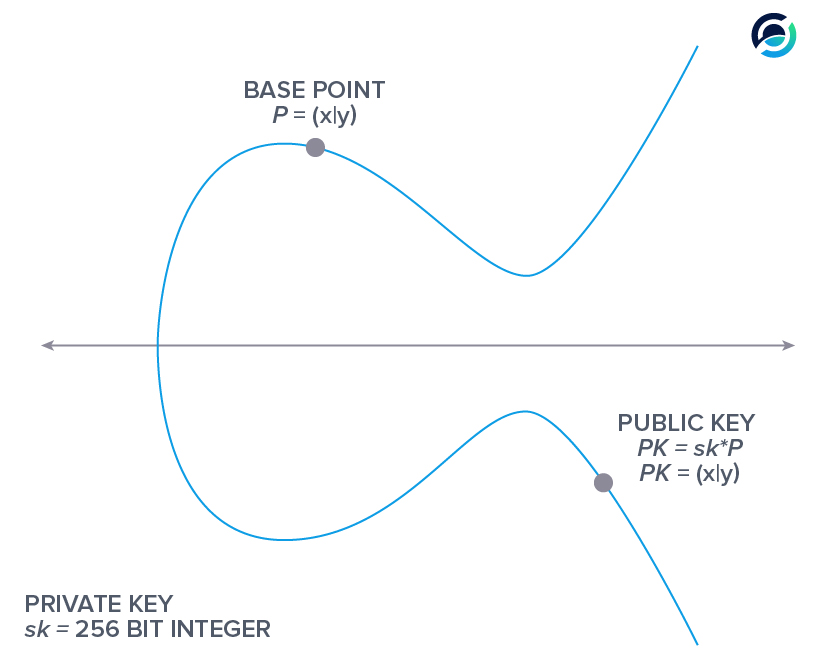

It is a convention that scalars are written with small letters, like the private key sk, while vectors are written with capital letters, like your the public key PK.

It’s important to note that the hash of a vector is a scalar. The hash function consumes the tuple of values as an input, and produces a scalar as an output.

We use the \(\bullet\) operator when we are referring to multiplication on the elliptic curve. We use the \(\cdot\) operator when we are referring to regular multiplication of scalars. We added this little discourse because it should help you to keep track of what values are points on the curve, vectors, and what values are scalars.

To recap our previous articles:

- Your secret or private key sk is a large random number.

- If you multiply the base point P used for the elliptic curve - secp256k1 - with a private key, you get a public key PK.

- You want to prove knowledge of sk to the network without revealing it.

Generating the Signature

Generating a digital signature in an elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) scheme is based on the distributive property for point addition.

\[n \bullet P + r \bullet P = (n + r) \bullet P\]We get the equation below by multiplying with \(\text{hash} (m, r \bullet P)\) on both sides and factoring out the base point P on the right side of the equation. This equation holds for any m, r and n.

\[\text{hash} (m, r \bullet P) \bullet n \bullet P + r \bullet P = (\text{hash}(m, r \bullet P) \cdot n+r) \bullet P\]We take it slowly from here, baby steps. For math-savvy readers this might mean some extra steps but we would like to keep this understandable for the widest audience possible.

We learned that your private key multiplied with the base point yields your public key.

\[sk \bullet P = PK\]We replace the universal variable n with our private key sk, and use PK to simplify the expression \(sk \bullet P\). Let’s do this in two steps, first replacing n:

\[\text{hash} (m, r \bullet P) \bullet {\color{red} sk} \bullet P + r \bullet P = (\text{hash}(m, r \bullet P) \cdot {\color{red} sk}+r) \bullet P\]and next simplifying \(sk \bullet P\) to PK:

\[\text{hash} (m, r \bullet P) \bullet {\color{red} PK} + r \bullet P = (\text{hash}(m, r \bullet P) \cdot sk+r) \bullet P\]Now, we will replace \(r \bullet P\) with R. This follows the convention that the scalar r multiplied with the base point P gives us a point on the curve, the vector R.

\[\text{hash} (m, {\color{red} R}) \bullet (PK + {\color{red} R}) = \text{hash}(m, {\color{red} R}) \cdot (sk+r) \bullet P\]We define s as..

\[s = \text{hash}(m,R) \cdot (sk + r)\]..and replace it accordingly. It should be clear that only a person in possession of the private key sk can compute s.

\[\text{hash}(m, R) \bullet (PK + R) = {\color{red} s} \bullet P\]This is the equation we will be working with from here to prove the following claim:

If you can provide an R and s together with a message m that satisfy the equation

\[\text{hash}(m, R) \bullet (PK + R) = s \bullet P\]This proves you know the private key sk that corresponds to the public key PK.

Two conditions must be met in order for this to be the case:

- If you know sk, then you must be able to provide working values for m, R, and s

- If you don’t know sk, then you must not be able to provide working values for m, R, and s.

Being Able to Provide a Valid Signature With the Private Key

Let’s assume you know sk.

First, you choose random value for r and a message m to sign. Next, you compute \(R = r \bullet P\). Lastly, you compute \(s = \text{hash}(m,R) \cdot (sk + r)\).

If you plug these values into the equation..

\[\text{hash}(m, R) \bullet (PK + R) = s \bullet P\]…from above, you get…

\[\text{hash} (m, r \bullet P) \bullet sk \bullet P + r \bullet P = (\text{hash}(m, r \bullet P) \cdot sk+r) \bullet P\]…which we said earlier holds for any m, r, and sk, formerly n. This satisfies the first condition we need to prove our claim.

Not Being Able to Provide a Signature Without the Private Key

Now we need to prove the second condition is met as well: If you don’t know sk, then you must not be able to provide working values for m, R, and s. In order to provide these working values you would have to solve the equation below:

\[\text{hash}(m, R) \bullet (PK + R) = s \bullet P\]To do so, you would need to break the preimage resistance property, one-wayness, of the hash function. This means that you would have to find inputs to the hash function, specifically an m and R, that produce a certain output.

Because blockchains use strong preimage resistant cryptographic hash functions, this proves our second claim. You cannot provide working values for m, R, and s if you don’t know sk.

Not Revealing Information About the Private Key

Now we only need to make sure a potential adversary doesn’t learn anything about sk from publishing s. The message m and the point R are entirely independent of sk. Only s could potentially reveal anything useful about sk…

\[s = \text{hash}(m,R) \cdot (sk + r)\]…but in order to derive sk from s one would have to solve for:

\[sk = \frac{s}{\text{hash}(m,R)} - r\]An adversary doesn’t know r and cannot derive it from R - discrete log problem - as it would be the same as deriving sk from PK. Without knowledge of r you cannot compute sk from s.

Quick Recap

To recap what we did:

- First, we used the distributive property to build an equality.

- Next, we multiplied both sides with with \(\text{hash} (m, r \bullet P)\).

- We replaced the variable n with our private key sk and the expression \(sk \bullet P\) which represents the product of our private key sk with the base point P with the public key PK.

- We defined R to be the product \(r \bullet P\).

- We defined s as the term \(\text{hash}(m,R) \cdot (sk + r)\).

- We showed that if you can provide an m, R, and s that satisfy the resulting equation, it proofs knowledge of the private key sk corresponding to the public key PK.

- We also proved that without knowledge of sk, you cannot provide working values for m, R, and s.

- Lastly, we showed that you can reveal m, R, and s without revealing any information about the private key sk.

Verifying the Signature

All full nodes and mining nodes verify every transaction before forwarding it or including it in a block. They verify a transaction, or message m, based on the originating public key PK and the signature, which is composed of s and R. As we showed above, only by knowing sk one can produce a valid signature. Verification of the signature includes plugging those three variables into the equation below and checking if it holds.

\[\text{hash} (m,R) \bullet (PK + R) = s \bullet P\]In the context of cryptocurrencies, signatures are used to prove that you own a UTXO-set and that you are entitled to spend it. One spends a UTXO by creating a transaction and using it as an input to create one or more new outputs. Each input spent needs to be signed.

What the Digital Signature Looks Like

A transaction typically informs the network about a transfer of money or data. The message m is to be signed, with s and R comprising the signature of that message.

Because s depends on the message m, the verification process is only successful if two conditions are met: The sender of the message knows the private key sk used to generate the UTXO’s address AND the signature (R, s) was created for that specific transaction m.

With cryptocurrencies, the message m is the unsigned part of a transaction.

The digital signature of that transaction consists of the x-coordinate of R and the sign of its y-value. This x-coordinate is concatenated with s, a 256-bit integer, after they have been converted to hexadecimal format.

Each transaction output has a locking script. It is called scriptPubKey and requires certain conditions to be met in order for the recipient to spend it.

Summary

To summarize, public key cryptography (PKC) is used to verify ownership. It’s basic building blocks are private keys, public keys, and a digital signatures. This methodology is also used in encryption schemes such as TLS, PGP or SSH.

While there are many different PKC schemes, blockchains use elliptic curve cryptography (ECC). Cryptography mostly relies on one-way functions. The first one-way function we introduced was the hash function. ECC and its underlying discrete log problem pose a second one-way function.

We showed that multiplication on the curve, even with large numbers, is easy and computationally inexpensive. We also showed that division is computationally infeasible.

Next, we showed how an address is derived from a private key with the two most important steps being multiplication of the private key sk with a base point P to get the public key PK and then hashing PK to get an address. Because both multiplication and hashing are one-way functions, it is not possible to reverse this process.

We constructed the equation used to create and verify digital signatures and proved that only someone with knowledge of sk can produce a valid signature (R,s) for a given message m. We also showed that you cannot compute the private key sk from the information contained in s.